We’re really pleased to bring you something a little different! We’re utilising our brand new Podcast channel, Textile Talk, to bring you in depth interviews with inspiring artists. Our first guest, is a multidisciplinary artist specialising in computer-aided embroidery design. Her goal is to create an experience for the viewer that overwhelms with colour and transcends the quotidian. Her work encourages escapism and promotes pure sensation.

Textile Talk with Susan Hensel

Listen to the podcast now or read her interview below. Take a look at a small collection of her work and find out more about where and when you can see her work in upcoming shows.

About Susan Hensel

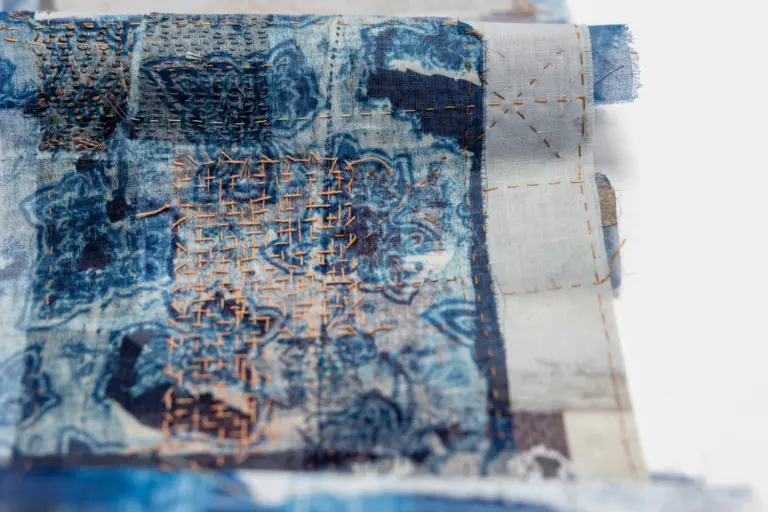

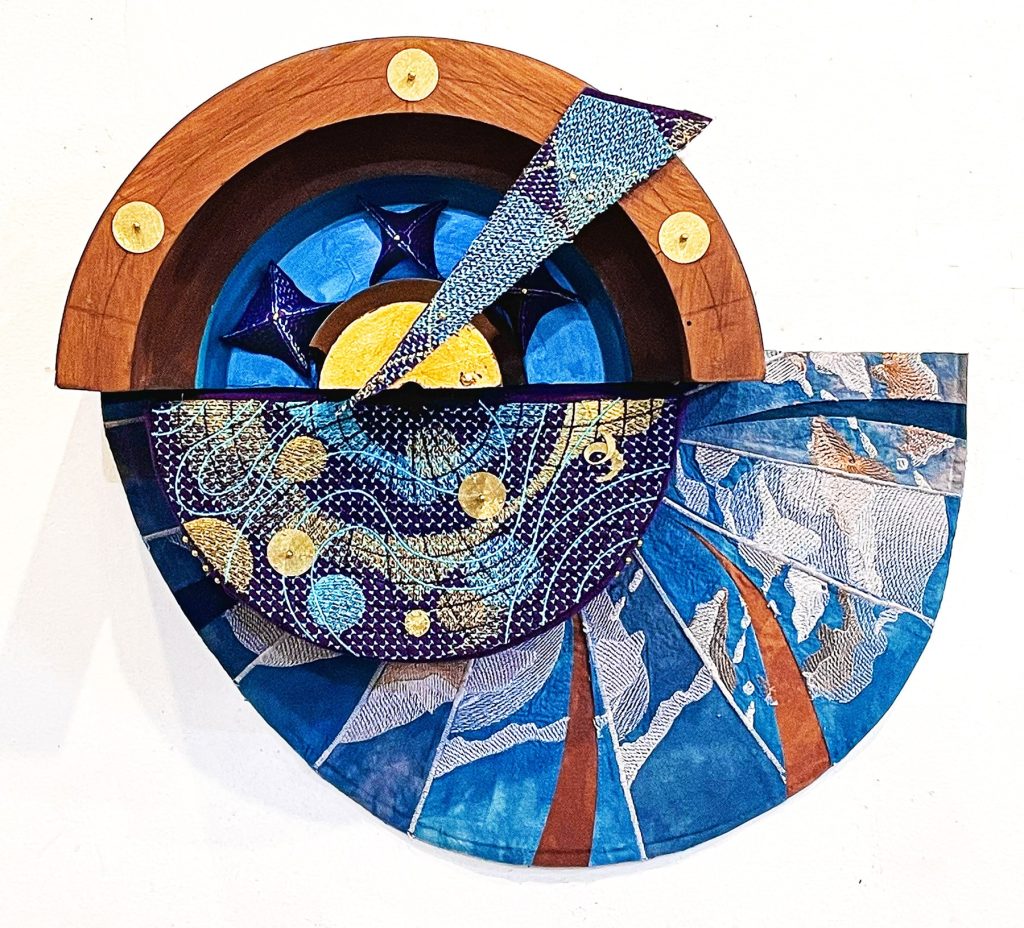

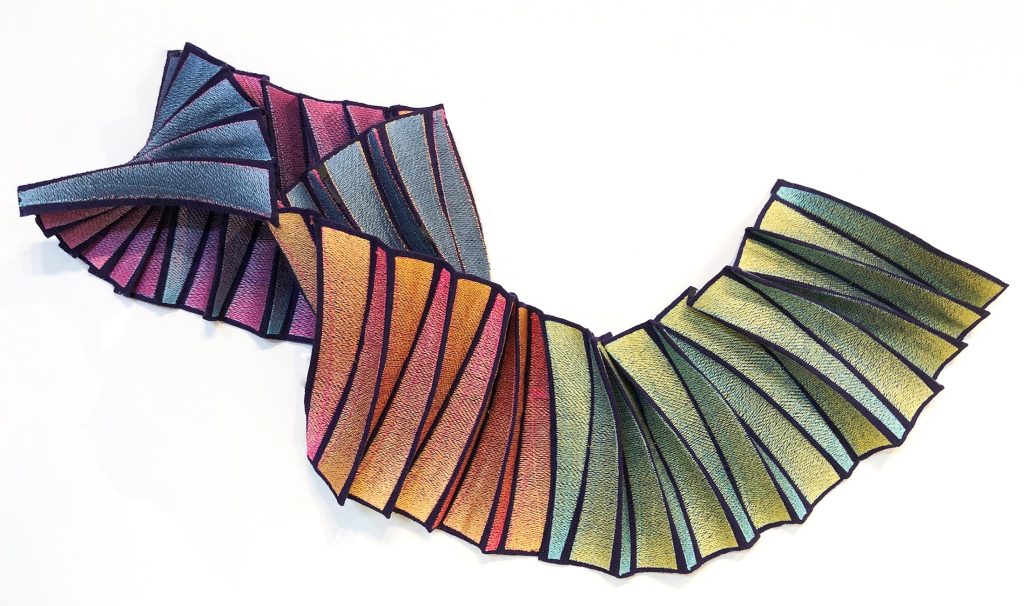

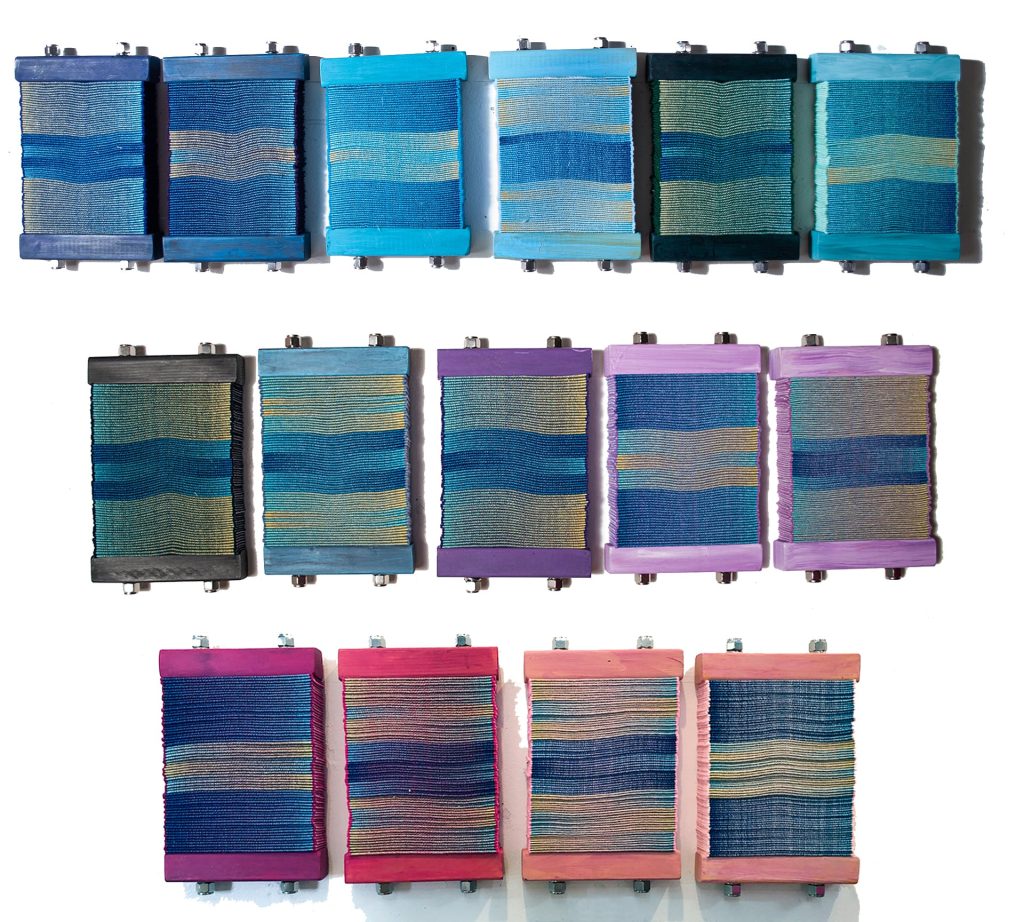

I make sculptural textile work combining mixed-media practices with fabric and embroidery across digital and manual platforms. I exploit the physics of light as it interacts with the structure of the triangular embroidery thread. The light scatters in multiple directions off the sides of the thread, creating different tones and saturations of the base colour.

I also exploit the science of optics, relying on our brain’s ability to optically mix spots of colour in close physical proximity. Further relying on the principles of colour as taught by Joseph Albers and Johannes Itten et al, I exploit the vibratory effects of complementary colours and close saturation split complements.

All of this creates a changeable optical environment activated by the viewer’s movement from side to side as they view the artwork. The viewer experience is one of puzzling beauty, playfulness and sometimes awe.

Interview with Susan Hensel

Hello, everyone, and a very warm welcome to this Textile Talk podcast. I’m Gail Cowley, and I’ll be your host today. Joining me is Susan Hensel, a multidisciplinary artist with a 50 year plus career who combines a mixed media practice with embroidery across digital and manual platforms. So, Susan, it’s lovely to have you with us. Thank you so much for agreeing to do this podcast.

Susan: I’m very pleased to be here. Thank you, Gail.

Gail: It’s a pleasure. So, I wonder if I could start off by asking if you could tell us more about the type of textiles you create and also the methods that you use?

Susan: Sure. I work in digital embroidery, which I’m pretty sure your students know what it is, but basically it is images or swathes of colour. In my case, designed in the computer and stitched out on a computer aided embroidery machine.

Typically, that’s used to make just simple images or monograms for clothing. But I’m trained as a sculptor, and as soon as I got a look at one of these machines, I knew that there was a way I could use it.

I’m highly technology oriented, having grown up with an engineer father in fifties, so I’m not scared of technology. He probably had the first graphing calculator on the face of the earth. I mean, gizmos and gadgets were everywhere in our house and where I grew up in Ithaca, New York, which is a home of Cornell University, we also had, in the early 1960s, computer classes in our secondary school would be high school in the United States. So I was exposed very early, so I didn’t have any of that fear going in.

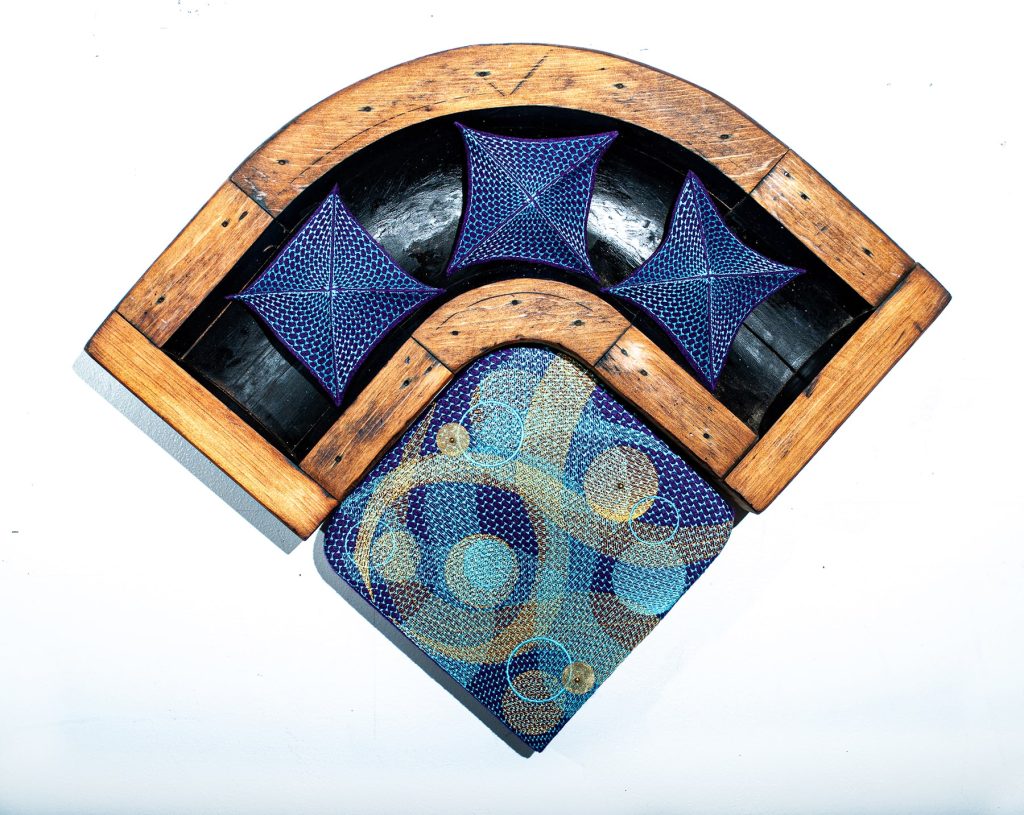

The things that I make sometimes they are pictorial, yes, but mostly I am making modules that are designed to bend into sculptures so they will have permanent folds, and that also are designed to shimmer at different points on the spectrum, depending on what direction you’re looking at them from. So they are a little bit perplexing in terms of colour. It’s a little hard to figure out how this is happening, but I’m making use of basic physics or the basic ways that our eyes mix things optically. I’m also making use of the particular feature of polyester embroidery thread, which is that it is basically a triangle cross section under the microscope.

Gail: How fascinating. I did not know that.

Susan: I didn’t know it either, but I had been noticing these unusual colour events happening in what I was experimenting with, and so I started exploring the history of the threads. And rayon thread is very round, and it’s very beautiful. It’s very lush, but it doesn’t scatter the colour in the same way that the polyester thread does. And that’s because of that triangular, more or less triangular shape.

And what that does is it makes the light bounce in multiple directions, and that’s where all colour comes from, is the bouncing of light off of a surface. So if the surface is blue. What bounces off is colours in the blue spectrum, but because this is triangular, it’ll bounce off at some really odd angles, which will take you further through the blue spectrum. You won’t get just one shade of blue, and that’s why it sparkles so much. And then I make use of what I’m stitching on, which is polyester felt, and I let that color show through.

So, I’m making all kinds of colour choices, and I’m usually only using two, maximum three different colors of thread on a purposefully chosen color of felt to get the shimmer that I want or the changeability that I want.

Gail: How much of that? I mean, that just sounds amazing to me, but I’m really interested to know how much of it you’re able to plan in ahead, or are you sort of hoping for a what I would term a happy accident, or is it something that you can actually plan for that you know, how it will look at the design stage?

Susan: Yes to both of those questions. In a way, there’s a tremendous amount of intuition that goes into this, much more than most people expect with a technology driven technique. But the longer I do this, the more I can predict what the colours are going to do. Discovering all of this about the thread was a combination of research and happy accidents.

I noticed something happening and I wanted to be able to get more of a handle on it. But that being said, there are all kinds of accidents that happen, including choosing the wrong thread cone when you’re setting up the machine. I have 15 colours of thread on there, but I’m only using two or three of them. And it’s real easy to choose cone number one when you meant to choose cone number two when you’re setting it up. And sometimes those happy accidents take you places, too.

Gail: Yeah, I’m sure. I suppose my next question will be, what sort of machine are you using? Because it doesn’t sound like anything that I think many of our listeners would use.

Susan: Yeah, I started out on a single needle embroidery machine that had a computer in it, and it was not a very good machine. I think I just had a lemon, to tell you the truth. It’s a good brand, but that particular machine had problems. But I learned how to do it in there. And I also learned that with a single needle machine, you’re going to spend all your time changing the threads by hand, threading and rethreading, threading and rethreading. So I went from that to a ten needle brother machine, which allows me to do automatic colour changes, because when you put the design in the machine, you then tell the machine, on this step, it’s supposed to be red, on step two, it’s supposed to be blue, and you just key it in. It’s really quite easy to do.

And now, most of my work is done on a ricoma 15 needle machine. And the reason I use this machine is because it’s got a very, very, very large hoop. I can make modules that are 1820 inches by up to almost 48 inches wide.

Gail: That is large, isn’t that?

Susan: It really is. When I found that machine, it was really worth it to me to take out the loan to get it. And I paid off the loan on the ten needle machine, whose maximum size is about seven inches by ten inches.

Gail: Which is going to be very limiting.

Susan: It’s very limiting. And so, working on that machine, I learned to work modularly so that I could build things into larger objects. And I apply that same technique to this humongous hoop I’ll be delivering tomorrow. Packing up today three wall mounted sculptures that are 96 inches tall. Reason I can do that is because I can work in modules and then sew the modules together and then attach them to armatures.

Gail: Yes. What sort of armatures do you use? Are you using wire?

Susan: No, I usually am building a combination of foam core board, a nice thick foam core on a plywood base, and then usually just that very thin plywood, like we use underneath tile floors, which would be half a centimetre, maybe. I’m not sure.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And then to keep it from warping, you need to put a frame of some sort on the back. So just thin strips of wood built into a square like you would for a canvas, but a fix to the back to keep it stable so I can pin the fabric down as I glue it in place. And sometimes the pins are a decorative element. I’ll use found objects. I’ll carve walnut if I need walnut. It’s such a beautiful wood. And I’ll use what I need to get to where I’m going.

And where I’m going at first is driven by colour. There’s no question. I mean, these colours and colour combinations drive me forward. So I stay with one colour combination for a very long time because it suggests more ways to be. So that’s why there’s so much blue in my work right now, because I’ve been working with this blue and gold and purple combination that just flies into your eyeballs somehow. And it suggested issues about climate change and water health and things like that.

Gail: Which is obviously very of the moment, isn’t it? I think we’re all very aware just now of some of the problems and the planet surrounding us.

Susan: Oh, yeah. The planet will outlive us. But in the meantime, let’s see what we can do to live with.

Gail: Absolutely. I’ve really enjoyed looking at the photos you sent me, and I also realized that you had some gorgeous wooden framework. Is that the walnut that you carve yourself?

Susan: Yes, it is.

Gail: My goodness, you have many talents.

Susan: Well, like I said earlier, I was trained as a sculptor. My majors in college. I have two majors and one was sculpture and the other was painting. And I’m not a particularly good painter, but I can apply those skills as needed. I can mix colour that works and things like that. But I’m not in love with the paintiness of paint.

Gail: I can sympathize with that because when I was at university of my first degree, I did a design degree and we had to go across four different subjects so we did ceramics, forge, metal and textiles. And I think getting that breadth and depth and bringing other materials into your work, it really adds another dimension, doesn’t it?

Susan: It does. I don’t believe that it is necessary to stay with one media. For me, for some people it is, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But for me I’m always seeking to use the medium that expresses what I need to express. And I’m very willing, obviously when you look at things, to combine them. I put plumbing parts in there in the hardware stores. Little brass screens and washers and things I find on the ground. The world is the oyster.

Gail: Do you have a very large area that you can have all of these things out together? Your machine, all of the different materials and objects that you may use? You must need a very large studio area.

Susan: I need probably more than I have. I get claustrophobic. But I own an old building, old for the US. It’s a little over 100 years old and I live in a two-bedroom apartment upstairs. The first floor is my main studio and the footprint is about 1000 sqft. But the usable area is closer to 800. And then there’s a basement where I have my wood shop and we also build boxes down there. And part of my wood shop is in the garage.

Gail: That sounds wonderful doesn’t it? To have so much space?

Susan: Oh, but I can’t tell you, Gail, how much I wish all of it was on one floor and that it was 3000 sqft.

Gail: Wonderful.

Susan: What I do not have enough of is wall space or storage space. So when you think of things being 96 inches tall, that takes up a lot of wall space. I have to clear the wall to take the photograph of it, of course. And everything has to be photographed and documented and inventory. And because it’s textiles and wood and things, I cannot store it in a mouldy basement.

Gail: No, of course. No damp or anything like that.

Susan: Yeah. So I have to use professional storage, which is wonderful. And I’m actually going there today to deliver back some things that have been on exhibition and a couple of new things and then to pick up a lot of pieces that are going out tomorrow to a large exhibition. But what’s wonderful about this professional storage, they meet me at the bay door and they have all the boxes ready for me and they put them in my rental van. This is so wonderful. I can’t tell you.

Gail: Oh, I’m sure it just sounds like a dream.

Susan: I have to pay for it. But once I started working in textiles, and when I started working in textiles that were three dimensional, I had to build specific kinds of boxes so they could ship, and I had to protect them from wild temperature and humidity changes. And these aren’t really textiles or on Armatures. Most of them think of that when I started.

Gail: No, I don’t think any of us ever anticipate the sort of room that we’re going to need in June, do we?

Susan: Yeah.

Gail: I know that you’re a gallery director as well. We often hear that textiles are very much considered to be the poor cousin of art and not valued quite as highly. Would you agree with that?

Susan: Not at all, no. Some of it comes from us. The blue chip galleries are showing textiles. I don’t always think they’re showing the best, because I don’t think they know what they’re looking at sometimes, but they are pushing them a lot in the last few years. But I had an interesting conversation a few years ago. It was before the Pandemic hit.

I had flown to Florida to attend a learning convention with the Ricoma manufacturers, and so they had training for us on using our machines, taking apart our machines and putting them back together and speakers coming in to talk to us about putting pictures on our hoodies. And I had so many people say to me, oh, well, I’m not an artist, you’re an artist. I said, no, what you’re doing is also creative. We’re doing the same kinds of things. I’m just across the street from you, we’re next door. I’m just doing it a little differently. So some of that comes from us. Oh, I’m only a textile worker, I’m only an embroiderer. And I’m guilty of it too. Trust me, I am.

But, you know, I’m only a 72 year old Midwestern artist. Yeah. The only is what we need to work to get rid of what we do is important. And there are people who focus on the historic nature of our medium, unbelievable people, and that great value. And if it is historical reproduction, it has its place in the market, in history museums, in university museums and university collections and textile museums. It’s got its place and it is fundamentally sound.

And then there are the people who take it to a different place and it’s not further, it’s just different. And it might be the kinds of things I mean, this is where a lot of us start. It might be the kinds of things that you take to sidewalk shows or to your local festivals or your local fairs. And those are the more utilitarian things, mostly, or the things that a lot of people can identify with.

Maybe the imagery is something that nine out of ten people will love, because they recognize it, it does things for them, but then if your work doesn’t fit in that section, then you have to start looking at galleries and universities and things like that, and that’s kind of what happened to me, and it’s also a part of that thing for all of us as makers. When you run out of friends and family to give things to, I’m sure.

Gail: A lot of people will resonate with that. Yes.

Susan: Most of us who are out in the world in what looks like a bigger way, that’s how we got there. It was like tearing our hair out, going, what am I going to do.

Gail: With all this stuff? How did you make that leap? Because it is quite a leap, isn’t it?

Susan: It’s a huge leap, and I don’t know. I am very, very successful at getting the work seen, and I see the work as doing its work in the world, because I firmly believe that what we do is extremely important.

As human beings, we’ve marked our objects since probably before language, right? Something humans do, whether it’s for magic, for identifying it as our object, for religious purposes, or just because we’ve always fundamentally done these things. And so the objects have resonance, and that resonance needs to be shared. And so I’ve got all these beautiful objects that, when they’re doing their work, help make people slow down and go, oh. And that’s what all of us need in this hyped up world. I do sell some, but I haven’t found the sweet spot yet, to tell you the truth. But I sure know how to get shows, and I can get them in universities, I can get them in kind of like b list galleries. And definitely all the proliferation of online shows are all kinds of things now.

Gail: Yes. Over the pandemic, over the last two, two and a half years, when the world just changed around us, really, so much went online, and we suddenly started to see a lot of things that we would have visited, such as shows, galleries, suddenly became more of an online event. Did you notice changes going on during that time and the way that you work with the way that you displayed your work?

Susan: Yes, huge changes. When the pandemic hit in the US. And we had our first shutdowns, every single one of my shows that was scheduled for the coming year was either cancelled or delayed two or three times.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: Talking everything.

Gail: Yeah. It’s just shocking, isn’t it? The way that everything just came to a halt.

Susan: Yeah, everything. And meanwhile, I had been working for a couple of years with the agency in Florida, and I said to them, I’ve got to get people into my website because I’ve got so much stuff. I think what I want to do is small online shows on my website. And so they trained me up, and I started doing that. So I kind of started doing that just a few months into the pandemic because I had to find a way to take control of something, anything. You know that feeling?

Gail: Absolutely. It’s all getting away from us, didn’t it?

Susan: Yeah. And so that was kind of my entry. And then on the flip side of that, I’ve been a gallery director on and off for probably 30, 35 years. And I knew about Artsy.net. I certainly had used it for a long time just to look at art and do research about artists and to read their written materials. It’s a very, very good website. It was the first online gallery specific website to present artwork internationally from established galleries. Individuals don’t get individual pages there. Galleries get pages on there. And I suddenly thought, well, how much does this cost? I have a gallery. And I had closed down most of the gallery program here in the bricks and mortar building because I really needed to return to the studio.

And so I continued putting people in my shop windows because they’re very large, I can’t leave them empty. And I looked into Artsy, and it took a while for them to get back with me, but it was within my budgetary constraints. So I reopened the programming of Susan Hence gallery at that point focusing on artists from the Midwest. So from Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, that kind of area, and who had a particular focus on materiality, who were driven by the action of what they were doing.

And so I’m showing people who often would be found in the craft area. I have Martha Byrd, who’s a very abstracted basket maker. I’ve got Christopher Rowley, who does Tufting. And now that’s rugged stuff, but not in his hands, the nature of what he does. He’s actually doing a punch needle style, but he’s thinking about getting a tusking gun, oranges stuff. I have a printmaker who does hand stitching with her prints. And I’ve admired her work for years. And I’ve got a painter out of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan who is a colourist like I’ve never seen before. Just astonishing work. Her name is Linda Ferguson and a dear friend because, you know, you have to be nice, dear friends, but she’s wonderful, wonderful, wonderful. Kim Matthews, who is an astonishing sculptor and colourist

So I’ve got this group of like, six or seven people. Daphne Koop, who works in found wood that she carves, and she makes small and large wall pieces, so they function as abstract paintings, but they’re heavily carved. There are insects of broken glass, and they’re coloured, and all kinds of things happen and just gorgeous things, and started promoting that. And little by little, we’ve been at it two years, and we’ve doubled the eyes on the work at a few sales. And the next step in year three will be to begin to specify these artists to my list of art consultants, because I also work with art consultants from time to time.

Gail: I’m really interested to hear you sort of talk about the kind of timescale that that takes. Very often when I speak with our students, I hope I’m not being too derogatory to them, but they very often are expecting something to happen, I would say overnight, but, you know, within a month or two. And it’s really interesting to hear you just express just how long some of these things can take from originally starting to coming to fruition and, in fact, be able to make any money out of them as well.

Susan: But the other thing that your students need to know I mean, there are a couple of things. It does take time, but most of the really famous artists that we can think of, with the exception of megastars like Damien Hirst, most of them have university jobs.

Yes, most artists have jobs. Even Feldia Barlow, who has shown at the Vet Espionale, who’s shown all over the world, is carried by, I think, three or four galleries. She’s got a fulltime job in college.

Gail: Yeah. Which is mixed with hard work, isn’t it? You have to be committed. You have to be committed to do that well.

Susan: And there are ways to do it. Part of it is it’s kind of a paradigm shift, because I deal with this with my artists and with artists in general, because I mentor also. And your art can be your career, but your career doesn’t necessarily pay your bills.

Gail: Yes, very true. Okay.

Susan: You hope that it can at least pay its expenses or whatever you have budgeted for it, and then you have a job, which you may also love. Of course, you might be two parallel careers, but that’s the norm. That absolutely is the norm, and one.

Gail: Often crosspollinates with the other, doesn’t it? I think if you would well, my personal view would be that if I was spending all day, every day creating, I think I would find that quite challenging. Whereas sometimes just having that change in between how you spend your days, what you spend them doing, one can actually cross pollinate one section of your life and cross pollinate with the other and make the whole thing a richer experience around.

Susan: Yeah. For me, the transitions between the two are difficult. But what I find is that my day, any actively exhibiting artist day, whether they have an outside job or not, has a tremendous amount of administration in it. And so we have to, you know, you have to carve out time with the materials.

I happen to be recovering from a serious injury which almost disabled me, and I have to have physical therapy, like, up to three appointments a week right now. Yeah. That definitely reduces my time in contact with materials. But I’ve applied some of the habits that I’ve been developing over the years toward productivity, and they’re two key ones for me. And it applies, frankly, to any independent field.

Pastors write to me saying, how do you do it? It’s just like what you do. You got to show up to write the sermon first. You’ve got to show up. And when I’ve mentored people who are trying to fulfill grants, I go, But I have a job and I’m so tired. I’m going, yeah, I know, but can you stop by the studio on the way home for ten minutes? Well, yeah. And if all you do is write a list for the next day or your shopping list, I don’t really care. But if you show up, you’ll begin to establish the habit of showing up.

Gail: That’s so true. So true. I know. With our students, sometimes they do. They struggle on keeping momentum going in, just as you say, you have a job and you’ve got kids very well.

Susan: I mean, one of the people I’m working with right now has a complex living situation. She lives in a multi generational household and she’s basically the caretaker for everybody.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And she has an outside job. She is a practicing artist, and there are plenty of times when she really can’t work on her work. And that’s okay. But one of my mantras also, beyond just showing up, is if you have five minutes, you use five minutes.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And then the other thing is there’s kind of like a four part to this claiming your space. Now, I’ve got a generous space. I wish it was larger. I’ve got a generous space. But if your space is a corner in your kitchen, own that space. If you have to put everything away six times a day, you’re never going to get anything done.

Gail: It’s very tough. I know. I often say to my students that if you can use ten minutes on the train. Perhaps in the way to work. To do a little bit of research. What is to plan the next time you’re able to spend time with material. Whatever it might be. And then try and plan perhaps longer sessions where you do get the machine up that afternoon. And if you have to take over the dining table or corner of the kitchen to do it. But then when you do it, you try and get the most out of it because you’ve thought about what you’re going to do in that period of time.

Susan: Absolutely. And that’s part of the showing up. And that time on the train is part of the showing up. It absolutely is.

Everything that we do in our lives affects what we do, and we all have complex lives. And the other thing that I know a lot of people struggle with is just taking it seriously. And it takes themselves seriously just because it is not an obvious immediate commodity like toilet paper. Right. We all understand those daily things, and we live in capitalist societies, your students and I, and our cultures tend to equate value with what things will sell for.

Gail: Yes, very true.

Susan: And there are other values involved here in addition to that, because certainly we all hope that we will sell some of this work. We all hope that it will go do its work in somebody’s home or in an institution. But there are a lot of ways our work can go do its work in the world. It can make the world a kinder, gentler place. I even remember this was something that came up to me a couple of weeks ago.

I was just talking to somebody, and it was like, what’s one of your deep memories of textiles? And it was of the embroidered pillowcases that my mother made. And as a child, I treasured those. Now, do they belong in a museum somewhere? No, these were purchased designs. But what they did for me as a child was that they brought me peace, they brought me beauty, they brought me texture, because I’ve always been very tactile, and they brought me my mother’s love.

Gail: Oh, absolutely. Yes. Both my mother and my godmother were embroidery teachers. So it was something that I grew up with. And for me as well. It was also a way of spending time with them. Because I would perhaps it might just have been a small cheat kit that I’ve been bought. But it would mean that I could ask them to show me a stitch to correct something I’d done. And I could spend real quality time with that.

Susan: Well, you know, this other part of textiles in particular is part of a deep history of making that’s really kind of extraordinary when you allow yourself to think about it. I studied with a dire spinner weaver named Judith McKenzie, and one of the most profound things that she ever said that has just stuck with me. And it had to do with the fact that we are physically in touch with textiles from birth to death.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: We’re born and we’re swaddled, wear clothing, we sleep it in bed linens, and we’re buried in a shroud, essentially. Wow.

Gail: Yeah, that’s quite a thought. I had never considered it in that way before, but it is quite a thought when I hear you say that.

Susan: Yeah, I hadn’t either. Until she said it. I was like, oh, my goodness, she’s right. And the history of this, because I’m also a spinner and a dyer, although I haven’t been spinning as much the last couple of years. But, you know, the discovery of all these things is remarkable.

And it’s because we’re fiddlers, you know, I mean, fiddlers. It’s built into the human body, I guess is just diddle with this leaf. Oh, look, there’s something inside it. Fiddle, fiddle, fiddle with this cocoon. Oh, look, it’s a thread. It’s that thing. That thing is interesting. It’s that fiddling that we do.

Gail: It’s true. And I don’t know, textiles does take up a huge part of our lives, whether we know it or not, or we’re actually aware of it on a daily basis or not. Memory. There. As well as you’re saying if you were there’s, pillowcases.

Susan: I haven’t thought of those pillowcases in years. And I was just talking with an embroider and I was like, oh, I remember. And it’s an early memory, probably four years old or so is what I remember it from. I always wanted those pillowcases.

Gail: I remember they weren’t actually embroidered, but I do remember having some lovely brushed cotton sheets when I was very small. Felt gorgeous against your skin as a child. Really smooth, really warm. So, yes, I think we all have early memories of textiles in some form or other.

Susan: Yeah. And we just don’t realize it because they’re so ubiquitous.

Gail: One of the other things that I really wanted to ask you was about what you’re working on right now. I know that you have an exhibition coming up. Lovely. If you could tell us a little bit about that, because I’m sure that some of the listeners would like to either view or visit or could they visit online?

Susan: I hope they will be able to. The show is called At Play in the Fields of Colour Perception, and it’s actually part of a body of work that is beginning to travel. And the way that happened is because two agencies said yes, and another one called me and begged for it. So that’s cool. Yeah, that’s how you make traveling shows. You develop bodies of work and then you start pitching it places. So this is a local civic gallery theater complex, and it’s one of the larger ones in the area. And they have a very strong art program. And I will have something like 35 pieces in the very large public lobby of this building.

I can’t remember how many feet long it is, but it’s very, very long. And it will be seen from the street. And then there’s an upstairs lobby someone else will have. And then there’s an interior gallery, which is the members show this time. And I’m excited about the work. This is almost retrospective in nature. Most of the work was done during the pandemic, a little bit just prior.

I think the earliest work in the show is 2019, but most of it was done during 2021 and 2022. And it involves two major bodies of work, the Chromatic Group, which is working across the colour wheel with some of the colour effects I was talking about earlier. And then the second half of the group is what I call the Neo Tectonic period. And that has to do with climate change and it’s recent earth changes is what neo tectonics means. And those are the more multimedia pieces. That’s where you’ll see the textiles with walnut or with antique pipe molds, of all things that I discovered a few years ago. And then there’s some pieces in between that will kind of connect it’s all sculptural. None of it is all hangs on the wall because it has to be wall work here and none of it has a classic frame. And I love this stuff, and I actually love this setup because the only way to look at it is to walk along the wall and if people are paying attention, they’ll begin to see the colour changes, which is just lovely.

Gail: I suppose that going back a little way to what we were talking about previously regarding online shows and the changes that happen during the pandemic. You just can’t see it online. You have to be there. It is an experience in itself. Yeah.

Susan: Well, the other thing is, at the moment, I don’t remember entirely what images I sent you, but some of the most striking images are from the Chromatic series. They look monumental, and a couple of them are, but a lot of them are only about the width of my shoulders. Yeah, they’re quite modest, and so photography can mislead you. What I’m hoping with this show at play in the fields of colour perception is that they will do a video and I will send you a link. If they do, they usually do with their shows.

Gail: Oh, that would be great.

Susan: And often interview the artists because I’ve worked with this group before and I’ve been a juror for them before. It’s the Hopkins Center for the Arts, and I deliver the work tomorrow and they hang it, thankfully. And the opening is Thursday night, just a couple of nights from now. So by the time this podcast goes live, it will be up wonderful.

Gail: So will you be there on opening night?

Susan: Yes, I will. I’ll be the short old ladies probably sitting in a chair as much as possible because it was my got injured. I’m doing very well, but I still got another six months or so to go.

Gail: Wow, that’s quite a time for you, isn’t it?

Susan: Oh, my goodness. It was shocking.

Gail: Oh, dear.

Susan: But you know what? That’s part of life, isn’t it? And all kinds of balls will be thrown through your window. Some of them are fun balls, some are cheap balls, some of them are baseballs, some are bowling balls. And that’s just life. And so you figure out, based on work habits I’m happiest when I’m with materials and when I’m playing with tools. I can’t tell you how ecstatic I was to cut wood.

Gail: But just from obviously from speaking to you over the relatively short amount of time, you obviously have an incredibly positive and can do attitude in general?

Susan: Yeah. I mean, I have to work at it. Have I cried buckets over this? Of course I have. I’m not a superwoman, but appearances to the contrary.

Gail: Do you ever take commissions?

Susan: I do, mainly through our consultants for, like, architectural environments. I was hired, I think it was last year, to do two substantial pieces for the new Four Seasons luxury boutique hotel here in Minneapolis.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And I was hired by somebody out of Atlanta, Georgia, to do it. So it was kind of funny to have to send it to Georgia when I knew it was going to be down the road.

Gail: Do you enjoy that as much? Do you find that?

Susan: No.

Gail: Yeah, because somebody else is obviously interfering slightly with the full creative process there, aren’t they?

Susan: Sometimes a lot.

Gail: Yeah, I can imagine.

Susan: Yeah. There can be a lot of micro. Managing that is frustrating. And there were changes I needed to make in this commission that I made them. And I don’t think that it hurt it, per se, but I think it would have been stronger artwork if I had been allowed to provide it in the way I wanted to.

Gail: Where the adjustments to do with the colours they wanted, why they wanted it.

Susan: To have a very subtle palette that they wanted me to work with. And what attracted them to my work was the colour play. Part of driving the colour play in this particular form, it’s the Chromatic Book Blocks form for people who want to look up my work.

When you look at the Chromatic Book Blocks that I have on my website, or I think I have some in Artsy net, they’re only in the whole display of, like, 30 of these things. There are only two thread colours, and then the base colour of the felt changes. And then the other thing that changes, but changes subtly is the wood pieces that act as a clamp, and that intensifies the change. And they wanted the wood pieces to just be frames that all match.

So what that meant was that the colour changes could not be as perceptible, and the work is fine. I stand by the work. But I was disappointed that I couldn’t take it to that next step. And I think it was just a matter of the designer not really understanding the process. And fine. You have to say fine. Okay.

Gail: Yeah. I think it’s quite a difficult thing to accept that when you work to commission, you really are having to check and you no longer have artistic control over it.

Susan: Now I work better as a lone wolf. There are certain things I make that can be reproduced, that can be colour shifted. And I’ve identified those for our consultants, created a private room for them to go to. These are the things that, within reason, I can change, either on scale or on colour.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And we will consult.

Gail: One of the things that students often ask us is, how do I go to a price for my work? How do I know what’s in charge? Do you have any insight into that for them?

Susan: Well, I think I may have just written about it, or maybe it’s in the next blog post coming up. The pricing is an odd one. When I worked in Clay, which I did for many years, and I worked the street festival circuit, I had a rough formula that I started with, which was an estimate of my cost of materials, which is always kind of loose, let’s face it.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: You measure your floss. I know.

Gail: No, I do have some students that do get very concerned and do measure their floss, and I’ve actually suggested that it would be easier to weigh it rather than measure it.

Susan: I mean, kudos, but boy, that is not me. I would come up with an estimate of what I thought it probably cost me to make it, and then I would multiply it by ten and see what that looked like, and that would be my wholesale. And then I would look at that, and I would look at the people out there and see what they were selling similar things for. Could I double that price? Because you really do need to first price it wholesale, and you shouldn’t sell it wholesale unless it’s for retail. It’s important if you are going to move on to galleries.

You may not know that yet, but if you’re going to move on to galleries, you must take into account the fact that they’re going to take up to 50% of the sale price. They have to pay so many expenses, and so you sell at that price, even out of your studio or at the street fair. You kind of have to work with what you see out there and what you think your costs are. And also there’s this other emotional thing, which is would it break my heart to sell it for that?

Gail: Yes. When you spent so long doing something, you want your work to be valued.

Susan: Yeah. And sometimes you just want to price it high because you want to live with it longer.

Gail: Yes, that’s true. You’re not quite ready to let it go yet.

Susan: Yeah, that’s true. We just want to live with it longer. And so it’s kind of oofy. But it’s real important, even as students, not to drastically undercut, like, the people who trained you. I don’t know where you are in the market, but if you have worked out in the marketplace now, your students shouldn’t be charging the same amount you do, but they shouldn’t be charging 10% of what you do, either. There is a student price, but it’s not 10% of the master price.

Gail: No, no.

Susan: Because that becomes offensive to their own work and also to the master. So it’s got to be somewhere in between.

Gail: I think very often students forget that you’ve just made a very helpful distinguishment there. I think that’s the word distinguishment between the fact that what you may sell it for as an artist and what it may need to go into a gallery for are two very, very different things.

Susan: Yes, they are. And that’s really important to know. There are artists who should be gallery artists. Okay. That’s where their work belongs. And they have lost their gallery representation by selling at a discount out of their studios to clients.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: I mean, it’s fine to sell a discount to your family. Nobody cares. And to your closest friends or to trade, I mean, that’s fine. But if your gallery, should you be represented, is spending money on, you have to pay their rent, their lights, their employees, and then they are promoting you. Advertising costs, openings cost, being open, everyday costs, having people on the floor saying, I really think you should buy, sell, and sells work costs money. And so you are taking their money away, their legitimate money away, by selling out of your studio at a discount.

Gail: I have a friend who has a gallery, or has a gallery seven years ago, and one of his biggest annoyances was that after they had finished doing a show, he would hear people going around during the show saying that, well, I won’t buy it here. I’ll contact the artist later on and see how much discount I can get. So that was one of his biggest bugbears about us.

Susan: Oh, that’s fine too. I mean, your price should be your price should be your price. And then the good news is, when you sell it yourself, wow, you’ve made more money.

Gail: Yes. Yes. And that helps pay for all the.

Susan: Things that don’t sell right away.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: So, I mean, just look at it that way and just understand that galleries are in business. And when I still had people coming in to see other people’s work inside my building, I can remember very clearly somebody saying, oh, I’m just going to go to her studio. I can get a better price. I’m like, no, actually, you can’t.

Gail: Yeah. I think from the gallery owner’s perspective, if you can say that with complete confidence, you can’t be, I know this person won’t do that to me, then that’s great. But it also means that as you obviously already have, you build up people around you. You work with artists that you know won’t do that, and the ones that do, then you’re not going to continue to work.

Susan: No, there are people I will not work with because of that or because of unreliability, that kind of stuff. I’m just going to drop this in here for your students, too, just because this is a gallery director thing. What’s the value of a resume? There are two values to them. I mean, for the gallery, a record of shows, it doesn’t even matter how rinky **** they are initially. Okay. A record of exhibitions shows that you are serious and that you follow through.

Gail: Yeah.

Susan: And then reading other people’s resumes for an artist gives you ideas of where you should be looking.

Gail: Absolutely, yes. If you can see somebody that is in a similar field to yourself, that is aiming at a similar audience, then seeing that our resume is really interesting, it should be really useful to you as well. Just starting out.

Susan: Yeah. You can see somebody’s trajectory, and if their work appeals to you, in some way, you can use it as a bit of a roadmap. Very helpful. And I didn’t figure that out till I was in my 50s. Jeez. Learn it now.

Gail: I’m sure they will. Susan, it has been an absolute pleasure. I know that one of the last things I put onto the notes that we’ve exchanged is if you have a funny story or an anecdote that you’d like us to hear?

Susan: Well, this one is my classic one. Right now, how on earth did I start doing computer aided machine embroidery? I went to the state fair, Gale, and the Minnesota State Fair is huge. It’s almost the size of a world’s fair. And one year when I went, I decided to go to the building where they demonstrate knives and food storage systems, and I turned a corner, and there was Donald Duck being stitched out on a hands free embroidery machine. And it just mesmerized. Me. Not because it was hands free and not because it was Donald Duck, but because it was a blue like no other blue I had ever seen in my life.

And at that point, I decided I had to start working with machine embroidery, and it was clearly an epiphany. And so I did everything I could to get a grant to get the machine. No, I had to get a loan. But I did finally get a grant to get my first set of software to learn how to digitize and then provide an exhibition from it. But we can all blame the Minnesota State Fair and Donald Duck

Gail: Thank you. I will never look at Donald Duck in quite the same way. Oh.

Susan: It was like the most ultra marine blue I have ever seen. It’s my state fair love story.

Gail: Susan, thank you so much. It has been an absolute pleasure chatting with you this afternoon. It really has. Thank you so much for your time and just for your past wealth experience as well. I know that our students are all about business. We’re really enjoyed. So thank you.

Susan: Oh, well, thank you so much. You.

Upcoming Shows

2022

Thought/Process, Artistry, Bloomington, MN

Bending Toward Beauty,(solo) Hopkins Arts Center, MN, October 27 – December 3 2022

Bending Toward Beauty,(solo) Duluth Art Institute, MN, December 12, 2022 – March 13, 2023

Bending Toward Beauty, (solo)Artist Space online

“Fäden der Kunst.Werke in Fenstern,“ Leipzig, Germany, Zoe Schoofs and Susanna Baumgartner, October 2022

Current exhibition at the Hopkins Art Centre

2023

Women Take the Walls, Garret Museum of Art, IN

Bending toward Beauty, Springfield Art Association, Springfield, IL

Follow Susan Hensel

View her projects, online gallery, and make sure you follow her on Instagram.