We recently caught up with Textile Artist Allan Brown on our Podcast – Textile Talk. Following his wife’s death, he spent seven years making a dress entirely from locally foraged stinging nettles: A process he describes as ‘transformational’. His journey and process of creating the dress and its personal importance for him is being featured in a new film, The Nettle Dress. Inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans, the film is a modern fairy tale about the healing power of nature, craft and textiles. It’s out now in the UK and Ireland.

To celebrate the making and release of this beautiful and majestic film we caught up with the Allan Brown to find out more about the process of using nettles and organic fibres in textiles. Read on to watch the trailer, or listen to episode now to find out how you can also get with lots of various organic textiles groups.

Textile Talk with Allan Brown

Listen to the podcast now or read through the transcript below.

Textile Talk with Allan Brown

Transcription

Hello, everybody, and thank you for joining us on Textile Talk podcast. My name is Gail Cowley, and I’ll be your host today. Joining me for this episode is textile artist Allan Brown. Allan has spent seven years making a dress from scratch, using 14,400ft of thread, which has been made from the fibre of locally foraged stinging nettles.

In doing so, he relearns ancient crafts of foraging, spinning, weaving, cutting and sewing. Making a dress this way becomes devotional, helping Alan to survive the death of his wife, which leaves him and their four children bereft. The Nettle Dress is a film that has been made of this period of Alan’s life. It’s a modern fairy tale about the healing power of nature and craft. Directed by BAFTA nominated filmmaker Dylan Howard, it’s released by Dartmouth Films in cinemas across the UK and Ireland from September the 15, 2023.

Gail: I'm delighted to welcome you to Textile Talk podcast. Could I start off, perhaps by asking you just to give us a little insight into your background?

Allan: Yeah, sure. I studied fine art. Well, I attempted to study fine art after leaving school. I was at Goldsmiths for a bit, and I quit that. And I came to Brighton and did illustration and quit that and finally limped over the finishing line doing performing arts. But I had no textile background at all until I got enmeshed with the nettles. And that really just sent me off in a completely unexpected direction and one that I’ve just fully embraced and absolutely love it. I feel like I finally found my medium.

Gail: Why nettles? There obviously was a starting point somewhere where something sparked your interest.

Allan: Yes, there were a few threads, really. I mean, the most preseat one was we got a family dog, Bonnie. And I suddenly found myself out in the Sussex countryside exploring and walking, and I really, really loved it. And as I was walking around and I took wildflower ID books with me, starting to learn what plants gave you, what were edible and what had other healing uses or whatever. But I kept returning to nettles because it was well, they’re so ubiquitous. But also in my youth, I’d been shown how to twist nettle cordage, and I just sort of thought, man, I wonder if I can remember how to do that.

So I started fiddling around with nettles and remembered how to twist cordage, and I was starting to see how fine I could go. And in the process, I was sort of scraping away at the nettle bass that I was using and suddenly saw that within the bass were all these amazing super fine fibres that you don’t readily notice are there when you strip the skin off a nettle plant. So, yeah, that immediately got me interested, going, oh, my goodness, these look amazing.

They look like you could spin a really lovely thread from them. Not that I knew how to do that, but it just set me off on an inquiry as to whether nettles had been used to make textiles and if so, how was it done and when was it done? And I couldn’t really find many answers when I was starting out. And I think if someone had shown me a piece of nettle cloth at that point, my questions would have been answered and nothing further would have happened. But because I couldn’t find any extant examples of nettle cloth, I just thought, man, if I’m ever going to feel what nettle cloth feels like, I’m just going to have to work out how to do it myself. And, yeah, that really got me started.

Gail: And what does it feel like?

Allan: Well, now I’ve made and felt nettle cloth, it feels amazing. It feels very much like linen. The dress isn’t as fine a cloth as I’ve seen linen cloth spun and woven at, but it was definitely well, after a while, after quite a few years of experimentation, I finally got it to a point where I was like, oh, my word, this looks like it could be comfortable. And it looks really strong and, yeah, very much like a sort of medium rough linen.

Gail: Just from a practical point of view, we all think of nettles as stinging. How do you overcome that when you're picking them?

Allan: Well, the sting of a nettle is on the stalk, at any rate, is just these little hairs that like little hypodermic needle type hairs on the leaf and the stem. But once you scrape or flatten that by running it through a glove, or you can even do it with a naked hand, it just pushes those little stingy hairs flat, at which point it’s rendered docile. So, yeah, I mean, I usually wear gloves or just use a little square of leather and just wrap it around the stalk once I’ve cut it, and just pull all the foliage off. And in the process of doing that, it just flattens the hairs out and largely renders it non stinging at that point.

Gail: So when you go for your walks and you bring what, presumably a large bundle back?

Allan: Yes, that’s right. I mean, one of the things I really liked about the whole nettle process was that I could do so much of it on the move whilst out in the countryside, the tools, really, up until the weaving stage are so simple. Just drop, spindles, a little blunt table, kitchen knife to scrape the fibres once they’ve been retted.

I would often take a bundle of fibres that I’d stripped previously out on my next walk, so I could hand rub those while I was walking, or I’d be spinning fibre I’d already processed. Then I would harvest, search around, find the nettles that looked promising and harvest a bundle and, yeah, bring them back home with me. So I felt like both the walking to the nettles and the walking back from the nettles, I could still use that time to progress and actually work the fibres.

Gail: So it's really that immediate that you could pick them and then immediately start to work with them. There's no pre treatment that you have to do?

Allan: No, I mean when you can just strip off I call it green just when it’s just been freshly harvested. Not that the nettle itself is necessarily green, you get purple coloured nettles and green coloured nettles. But yeah, by green I just mean no previous processing and you can strip that off and scrape away the sort of vegetable gunk and get down to the fibres. But I actually ended up working a different way where I bring those stalks back home and then spread them out on the grass and dew rette them.

Retting is just an old word for rotting and it’s part of the process that we use in our other bast fibres like linen or flax and hemp. So yeah, I just leave them spread out on the grass and just the microorganisms in the soil, on the grass, in the air just sort of start to slightly rot the nettle. Not that you would notice necessarily that anything’s changed other than they’ve just dried out slightly, but that does actually change the handle of the fibre. And for the way I was working, you end up with a fibre much more like wool or flax or hemp toe without doing the retting. I find that the fibre is quite wiry, almost like fishing wire and I think that’s how our ancestors used it because it’s much, much stronger in that form. Retting does weaken the fibre slightly, but yeah, it just puts it into a consistency that’s much easier to spin.

Gail: I see. So I'm assuming that there will be a season to this that it wouldn't be something you'd be able to continue throughout the winter.

Allan: No, that’s right. I mean, I really harvest probably beginning of July through till end of August, maybe a little bit in September. That seems to be when the sort of sweet spot that the nettles are nice and tall and they haven’t started to degrade. I mean, in some parts of the world where nettles have been used, there seems to be a similarity to places where there was traditionally quite deep snow and the nettles would just be left standing and the snow would come and encase the nettles and just very slowly the snow would rette the nettles.

So in spring, just as the snow started to melt, you could go around and literally strip off the fibre from the plant and you’re ready to go. But unfortunately, here in southern England, our autumns are sort of wet and still quite warm. So the nettles just basically rot and come spring they’ve pretty much gone. So yeah, that’s why I kind of do a more directed retting process.

Gail: So would you sort of build up the fibres during the July, August, September and then do some of the weaving and that sort of thing over the winter.

Allan: Yeah, there was a sort of natural rhythm to it all. Yes. A lot of the summer months were just concerned with getting out, getting the nettles, getting them back and getting them retted, at which point they can just be stashed. I keep them indoors because I learned that nettles really absorb sort of ambient moisture and they tend to go mouldy if you leave them in an outbuilding or a garage. So, yeah, I have them inside but the fibres are still on the stalks. And then when I’m at a point where I need to process some more fibres for spinning, I will then strip the bast off the nettle and start the next steps in the processing. And they can sit in that form for as long as you need, really.

Gail: And then as far as making them into an actual cloth is concerned, how does that work?

Allan: So once the retting process is done, the main difference I found between nettles and hemp and flax, both of which I work with flax, I’ve been growing up my allotment and in the back garden for the last seven or eight years. But flax and hemp, the processing is a bit simpler because once you’ve retted and you just start to break the plant up, the core or the shy just falls away and what you’re left with is a fibre pretty much ready to spin. It needs to be combed or hackled just to get it into order. But with nettles I found that it requires an extra step because nettle bast or the skin has a sort of a bark.

You can’t really see it so much but it’s just a roughness. And I found that you need to scrape the fibres and get rid of that layer of bark which just comes away as a sort of dust. And then once you’ve done that, then yeah, I don’t hackle. The fibres are quite short by this stage. So I found just using wool carders does a really good job of just getting rid of any sort of unwanted bits of vegetable matter and the last of the dust. And then what you’re left with is just a very fluffy, pretty clean fibre which is just perfect for spinning. I just hold the little rolag in my hand and just spins straight off it.

I thought in the beginning that failing to preserve that long fibre was an issue because the beauty of hemp and flax is that it’s a lovely long fibre and that influences the way it hangs and the feel of the cloth. But I just realized that with nettles is just a shorter fibre and in fact, it’s convenient in many ways in that form because you don’t need to spin it off a distaff. You can just hold the rolag in your hand so it just makes it that little bit more portable. I’ve always got a bag of processed carded fibre and a drop spindle. And I can just spin whenever a moment presents itself.

Gail: And how much of that process did you already know and how much did you have to learn?

Allan: Oh, I had to learn it all. I mean, when I was trying to find out how to process nettles, the only information I could really find was on the Nepalese who use Himalayan Nettle they call Aloe, and they process it in quite an interesting way. They strip the fibre off and then they cook it in wood ash and make this sort of very alkaline sort of porridgey consistency which the fibres bubble away in. And then when they pull that out, they pack it with this sort of clay, which stops the fibres kind of felting or matting together. And I did try that with nettles, and various people have tried it to varying degrees of success.

But in the end, I kind of lent into flax and hemp processing because there’s just a lot more written about it as they were both kind of traditional European crops. And so, yeah, I tended to follow those steps even though nettle really just resists mechanization. I just found that none of the tools that you could use and flax and hemp really worked on nettle. Nettle just demanded that you kind of do it much more by hand. When you do it that way, it’s a little bit slower, but you get the results that you’re after.

Gail: So I seem to remember reading that you had started a group, an online group.

Allan: Yes. The nettle for Textiles Facebook group. I mean, how the film, the origins of the film came about by Dylan, my friend who directed the film. We were friends from going way back. He was just wanting to come over and check out his camera for his jobbing, TV work as a cameraman. And I said, man, while you’re here, do you mind if we just shoot a quick how to video just so I can share the process I’m using? Because I was chatting to a handful of people online and I thought it’d be easier just to show them rather than try and explain it with words. So we did that and we just chucked it online for free. And to our utter astonishment, it just got shared millions of times. And I was like, oh my word. Who would have thought that there was such interest in this incredibly niche area?

But I immediately thought that I should set up some sort of platform to pull all these people together, really, because even though nettle fibre is a very ancient cordage and textile fibre, it’s sort of a forgotten it’s largely been forgotten. And I just thought, well, with lots of people experimenting and researching and sharing their results collectively, we’ll be able to push things on much faster than us all working individually on our own. And yeah, I mean, that was lovely.

I connected with lots of people, some of which had been working with nettles for much longer than I had, and with my friend Bridget, who I met previously, was also into nettles. She set up a little website, also called Nettle for Textiles, where we just put all interesting historical and scientific papers on nettles up there and just sort of just gathered it all together to make it an easy searchable resource. So, yeah, that’s been wonderful. And that Facebook community is now 27,000 plus strong. Gosh with people producing some astonishing nettle textiles. It really has been wonderful.

Gail: Are nettles international. I mean, I can't say it's something I'd really considered before, but are they in every country?

Allan: Pretty much. I mean, nettle is quite a big family. I mean, Rami or Rami is of the nettle family. And that’s been a traditional textile crop sort yeah, in the east. But I think nettles are fairly ubiquitous across the world. There are lots of different species. We’ve got two or three different ones here in the UK. But, yeah, I think pretty much I mean, even in places like Kenya, which I didn’t imagine, they’ve actually got a very similar plant to the Himalayan nettle.

I don’t know what the geographical origins of that connections are, but yeah, no, nettle is very widespread and interestingly, where it has been used, or has been documented as being used, it seems to have been used in creating nets. So I think the etymology of nettle and nets isn’t accidental. And in fact, in a lot of European languages, nettle, needle, sewing, all share a similar route. And, yeah, I know this because I luckily met a woman called Gillian Adom early on in my research, and she wrote an amazing little book called From Sting to Spin, which was kind of written pretty much pre Internet, where she just set about trying to track down and follow all the historical hints and rumours about the use of nettle. And that was really helpful and interesting just to see how widespread its use was.

Gail: How long do you think that nettle has been used?

Allan: I imagine that it goes way, way back. I think in documented finds. We certainly know it was been used in sort of late Neolithic, early Bronze Age time. And that’s probably when I think Nestle was at its heyday. I mean, little scraps have been found in sort of Danish bog burials. I think there’s some nettle fibre been found on an arrowhead in Somerset from, I think, Neolithic times, maybe even earlier, I’m not sure. But, yeah, it’s just such an immediate cordage that it would have been so useful.

It’s almost like I mean, quite often when I’m out picking the nettles, I realize I’ve forgotten a bit of string or something to tie them up with, and within minutes, I can just roll some cordage and just tie the bundle of nettles up. And there have been times when I’m out with Bonnie and have forgotten her lead, and I just have to quickly rustle one up just to get into a cafe with her or whatever. So, yeah, obviously it’s seasonal, but certainly for the summer months, it’s right there. It’s like having a shop on your doorstep wherever you are.

Gail: I presume that you've experimented with colouring it.

Allan: Yes, that was a real revelation. I love natural dyeing, and you can get a colour from nettle. You can get a sort of yellow from the roots and various shades of green from the foliage. But what I discovered was, I think because it’s quite maybe because it’s a shorter fluffier fibre than flax or hemp, it really takes dye beautifully. It really soaks up the colour. So, yeah, that’s a real plus to it.

Gail: Yeah. No, I can imagine. And again, it's probably a really stupid question, but thinking about clothes, does it wash well? Have you tried?

Allan: Yes, I’ve washed the dress several times now. And the traditional way to do it is to either scour it, boil it in a little bit of washing soda or wood ash or something like that, and you can boil it. It behaves exactly as linen and hemp cloth. It’s probably stronger when it’s wet, but it’s very tough and hard wearing. And, yeah, it cleans beautifully and no degradation to the fibre or the cloth that I could see. And other than it’s just softening it up, when you first bring it out, it kind of goes a little bit stiff again, and then just in the wearing or the handling, it soon softens up.

Gail: At what point in the experimentation process did you decide that you wanted to make the dress out of it?

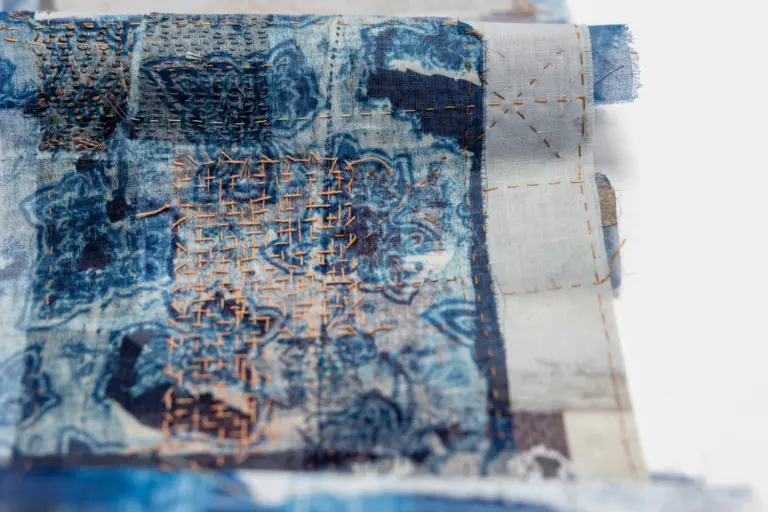

Allan: Yeah, I mean, I was a few years in, like, maybe sort of three years into the project, and I had woven a set of little samples. I started off just on a pin loom, and then as I taught myself the basics of weaving, put it on a small table loom, and, yeah, tried different attempts, and I learned how close the set affects the handle of the cloth. I mean, my first experiments, the little squares of cloth were like exfoliating scrubs. They were really rough, and I was quite disheartened that it was nothing as close to a wearable textile. But, yeah, as my processing got better and my spinning got better, I arrived at a point where I thought, man, yeah, this definitely would cut it as clothing. And I kind of thought it would be a shame to end this exploration just with a few little samples that sat in a drawer. It would just be so much cooler to actually see it through and make a garment and actually just physically feel directly what it takes to make a garment entirely by hand. So, yeah, I just started amassing fibres.

I wasn’t sure exactly what I was going to make, but I became aware of the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale about the girl who undoes an enchantment on her brothers who’ve been turned into swans by an evil stepmother. And yeah, she’s told that she has to well, a fairy tells her that if she spins seven cloaks or seven shirts, or eleven depending on the story, it’s quite an ancient story that the magic spell would be undone and her brothers would be returned to human form and she had to spin the nettles in silence.

She had to gather them from graveyards. I really started to identify with that girl in the story and how large her task was. And so I thought in the spirit of the fairy tale, it would be nice to sort of make a symbolic dress partly for her, really, just to honour her part in the fairy tale. But the fairy tale actually, I think did give me a couple of really helpful clues. I

think, like I said earlier, I thought that I must be doing something wrong in my processing, that I was ending up with short fibres and that it seemed to be so labour intensive. But I think usually in fairy tales it’s flax or linen that’s been referred to when you see them, when a spinning wheel comes into the story. But I did wonder whether nettles were used in this specific instance because there perhaps was a wider cultural knowledge at the time of that fairy tale that nettles were more hard work than the other bast fibres. And that sort of made me think, maybe I’m not doing something wrong. Maybe it just was a known fact that nettles are harder work than the other two. So it was kind of partly in honouring her that I just thought a dress would be the most fairy tale garment to make, really. So yeah, that’s when the idea of the nettle dress sort of came into my mind.

Gail: And that leads you into a whole other set of techniques that you have to find out about, I presume, because you're then adding dressmaking in.

Allan: Yes, that to me was definitely the scariest and the hardest part. And I signed up for adult education, sort of sewing basic classes and learned some useful stuff from that. I knew that I was always going to hand sew the dress because I just wanted to keep the whole thing sort of non machine based, just purely kind of just by hand. I looked at different patterns and what I eventually settled on was I call it a Viking pattern, but really it was this sort of typical linen undergarment that was really worn by men and women under their woolen clothing for a long period.

I think that basic pattern remained in use for hundreds of years. And what I really liked about it was that a it used quite a narrow width of cloth which looms back at that time were narrower, but also it was just a really low to no waist pattern. It was just using this thin, long length of cloth and all the cuts were just triangles in which every piece you got was just either turned around or placed in such a way that an address with fullness was created. But I knew how much work it was to even spin a skein of nettle yarn. So I thought, yeah, I definitely want a no waste pattern and one that I don’t have to weave or spin any more than I had to.

Actually, even before getting into this, I’ve always had an admiration for clothing. I just love the way a two dimensional textile can be created to fit three dimensional form and just became really interested in simple patterns that have been used at different places in the world at different times and the commonality between them. I did do a lot of practice. The main things I had to learn how to do were fitting a gore and just creating a gusset under the arms for flexibility and movement. And obviously, I’ve not been able to wear the dress. My daughter, Oonagh, is the one who has modelled it and wore it for the film. But she says it’s really comfortable and it looks great. I mean, it forms partly shaped by a belt, but, yeah, I really enjoyed the pattern.

Gail: Did, you know, have any input?

Allan: Yeah, she did. I mean, I made a couple of twirls in linen just to practice and we tried that on and, yeah, one way of doing a gusset just felt too bulky, so I kind of changed that slightly. And, yeah, making the twirls was a little bit difficult. I had to source in the final twirl, I had to try and source a linen that was going to be as close to the weight of the cloth that I was going to weave. And, I mean, that was interesting because when I use a modern linen, I could sort of fold a seam twice and hide the ends, but with the thicker nettle cloth, that just wasn’t possible. So I had to adjust how I was doing the seam slightly just so I could not create too much bulk.

Gail: So I know, obviously, that part of the theme within the film is that creating the dress helped you over your bereavement. I know that there will be people listening to this that will find themselves in a similar situation and will be looking perhaps have just lost somebody. I wonder if you could sort of, as much as you can, talk us through how that process worked for you.

Allan: Yeah, absolutely. Alex, my wife, I mean, she was actually a really good sewer. So even though I didn’t have any direct background, my mother was a sewer and a quilt maker and a knitter and Alex was a knitter and she was a really good sewer and she loved making costumes. And our kids always went off to school on World Book Day looking top of the bunch because she made some beautiful stuff for them. I felt there was that link. And really, when Alex got ill, just completely out of the blue, she was only 45.

We went to the doctor, she was having certain problems and neither of us thought for a minute that would be anything more serious. But, yeah, we got the diagnosis that it was cancer and pretty soon after that it was terminal cancer. That’s fine. She had just months to live, really, so that was a huge shock. And as she was going through chemotherapy and dealing, they did an operation. It was bowel cancer. So she had an operation to remove the section with the tumour in. Unfortunately, it was just too late that the operation didn’t work. But she was really amazing about it all. She just got her head round it completely quickly and she didn’t want anyone feeling sorry for her or moping. She just wanted it to be a happy time, that she would just live out the rest of her time as she wished. And she did that.

So, yeah, in the aftermath of her dying, also while she was having mean, when I first started spinning, I did just have an immediate visceral connection to the process. I just found it a really therapeutic and calming thing to do. But in the aftermath of Alex’s death, the spinning really just took on a whole deeper level of just something about it just really calmed my mind down. And if I was ever feeling overwhelmed or panicked, I’d just get the drop spindle out. And even it was just a few minutes, I could just feel this real tangibly. It was helping.

As I say in the film, I really feel like the nettles gave me a gift. That just the sheer act of processing, spinning them, obviously having to go out into the countryside to harvest them, that in itself was really good for me, just to get out, even it was only for a short period of time. And the spinning, yeah, it really served to sort of soak up the grief and also just give me a sense of forward motion. So I say in the film that the weaving of the cloth, on some levels it felt like it was a weaving of a shroud, but really Alex wouldn’t have wanted that. She really wanted us to look forward and move forward and embrace. Yeah. So it was partly a shroud in memory and honor of Alex, but it was also very much a garment that one of the children would wear and just a sense of turning that loss into something tangible and new and useful.

The dress took seven years all in all, from my first experiments right through to a woven cloth. But during Alex’s illness, and certainly for the two or three years following that, some days it may only just have been a few minutes of spinning was all that I could find time to do. But just that sense of moving forward was so. Helpful. And as we’ve taken the film out and done screenings around the place and met done Q and A’s after and I always bring the dress with me so people can handle and feel it and yeah, it’s just been really wonderful. So many people well, everyone suffers loss at some point, but it was just so interesting to note, especially as so many people in the audience were crafters how that’s such a common experience that knitting or just hand work really does serve to just hold you in a space where you’re not overwhelmed.

Both walking in the countryside, just being in nature and working with the fruits of nature just became so sort of central, really. At no point did anything in the process feel like drudgery. It just felt like it was a means to maintain a level headspace and so, yeah, the fact that there was a garment at the end of it all was almost like a wonderful bonus. But I think I would have been doing it just for the processing and the spinning, really just because I found it so helpful.

Gail: Yes, I think sometimes that, as you say, being outside, being in the fresh air and in the country does serve to ground you, doesn't it?

Allan: Absolutely.

Gail: But having something that a project that you can continue to work on when things get difficult I think is something that a lot of our students and our listeners would definitely empathize with.

Allan: Yeah. I mean, one thing I didn’t say, one of the threads that got me into Nettles is I’ve had an allotment for 30 years, and I’ve always grown at least some of my own food. And in a way, even though I didn’t really see the connection at the time, now I see that fibre and food are very much related, and traditionally, you would have grown both of those. And gardening is that similar thing of just actually getting your hands into the earth and feeling that sort of connection to nature and it sort of teaching you these really different skills. Like sometimes you need to get in there and dig out bramble roots which feels like you’re kind of going deep into your unconscious and pulling out these hard tendrils and then at other times you’re tending to a very delicate seedling. So it sort of requires all these different levels of input. And it was very much the same with textiles.

I mean, sometimes you’re dealing with very fine, delicate threads that you’re spinning where you need sort of sensitivity and then sometimes in the weaving it feels much stronger. You can feel this sort of tough, robust cloth coming out of it. So, yeah, gardening, walking in nature and the textiles, they all seem to give the same solace and we’re all kind of directly related to each other. And I do wonder with the production of textiles and food, that what we’ve given up for convenience.

We’ve actually lost these really fundamental skills that we’ve used for millennia, which really kind of ground us in a way which I think being untethered from those things or so removed from them, removed from them, I think it just puts us into a much more fragile headspace. And there’s something in the doing, in the making, where it’s really giving you something back over and beyond the actual garment or whatever it is you’re working on.

Gail: I suppose it's bringing us closer to nature as well. Isn't know, everything has its season, different things happen at the time they're meant to. It's a very natural process in the way that perhaps going shopping around Tesco's isn't?

Allan: Yeah, absolutely. And I think grief is very much like those things. There are seasons to it, there are rhythms to it, and there’s no real shortcut. You can’t shout at a tomato to grow faster than it wants to grow. So, yeah, it’s sort of just instilled a sense of just working with the natural rhythms and leaning into those.

Gail: And Allan, how did it go from sort of making, obviously, the cloth and then eventually the dress into then being made into a film?

Allan: How did that process come mean? Because Dylan had shot that original sort of how to video, which was called Nettle for Textiles, and we did a couple of other short films on nettles on different aspects. Like, we filmed the actual first woven bit of nettle cloth that I’d done and a bit of historical archaeological experiment that I was doing. So, yeah, we’d had a small body of work done and the success of that short nettle for textiles film really kind of alerted us to the fact that, well, there does seem to be an appetite out there for this. And I think once I got the idea that I wanted to make a dress, I said to Dill, not with the intention of making a film at all, really, but I just thought you should come and get some stock footage of a nettle cloth being woven. Because who knows when the next time that a large piece of nettle cloth will be woven? And it would be kind of good just to have it in the archives.

It may be useful at some point. That was the plan, but I was still some way off actually getting to the woven cloth. But Dill started coming around and just filming me out in nature, out in the countryside, around the house, the wonderful Sussex Downs, and, yeah, we just built up a little bit by bit and he ended up recording all the steps in the process and we thought maybe there would be another short film in it. But the more he gathered and the more the other threads, the grief, the loss of Alex, the things that were happening around the production of the class, those threads seemed like actually, hang on, maybe there is a wider story.

Even though I had no idea what shape the final film would. So Dill filmed it right the way through until the cloth was woven and the dress cut and sewn and we took and Oonagh wearing the dress, we went back into lime kiln wood, where a lot of the nettles were harvested from. And, yeah, there was just a sort of beautiful arc to the whole thing. And when Dill did the first cut, I was just sort of blown away, really, by how he had managed to just assemble all these parts. I mean, the central thread, of course, was just the process, just following the process. But I think the wider context just sort of gave it a greater depth, really. That’s how the film came into being.

Gail: I'm assuming that you've done some previews because there are some wonderful reviews on your site.

Allan: Yes, I mean, we didn’t at any point get any funding from the BBC or any production. What we ended up doing was we crowdfunded and a lot of those people that kindly donated towards just us covering the basic costs of camera gear and film and digital stuff came from that group. Even though the actual act of making it was quite solitary and my world was quite small at that point, just having to be at home a lot, to look after the children and stay on top of all the domestic side of things. There was this feeling of a sort of community, like wind under our wings sort of thing, who were buying into it. So we did an online screening at one point, mainly to the members of the group, and we raised a few further funds. So, yeah, we managed to get the film actually done.

The post production stuff was really what we needed, the funds for the sound and the colour grading and that sort of thing. Again, without any funding, we just started to approach cinemas. And again, really, the whole success of the film thus far has just been word of mouth and really the support of crafters and textile folk who were interested in the project. So, yeah, we’ve done 50 plus screenings just off our own back. Someone would say, I’ll be nice if you could play here. And we say, Is there a cinema there? And they’ve approached the cinema and then we’ve got in contact with the cinema and we’ve gone, shown the film, done a Q and A, taken the dress with us, and then those folk go and tell their friends.

Our marketing budget was literally zero. It’s all just been done through word of mouth and the support of the wider community. So that’s been really wonderful. And actually having physical screenings, we resisted just putting it straight online, mainly because it really felt like a gathering of the tribe. Each screening that we did, meeting folk in person afterwards, them being able to chat to us and feel the dress, it really felt like a celebration. So, yeah, we’ve just kept that going. And then just in the last month or two, we’ve finally got a distributor, Dartmouth Films stepped in. So, yeah, it’s just bumped up a level and we’ve got our national release, well, this week, actually, we’ve got the premiere tomorrow up in London, and then it’s going to be, in, goodness, 150 cinemas in the next couple of weeks. And that seems to be growing every day.

It’s completely wonderful and unexpected and I think just brilliant that a film that essentially deals really with craft and processing at its core has kind of broken through into a more mainstream platform. And I think its success really speaks to, I just think, a growing consciousness in so many people that fast fashion, the way we overproduce the huge wastage within the textile industry. I think this film’s just stumbled on and tapped into that. And I think possibly even the grief angle speaks to a sort of collective grief that we’re feeling about the difficulties, environmental impacts of how we live and looking at to see whether there are any parts of that process that we can really claim back and have more direct input into.

Gail: So if there was one thing that somebody could take away after they'd viewed the film, what would you like it to be?

Allan: I think it would be the sense of empowerment that you can get by claiming back even a symbolic connection to the clothing that you wear, just whether it’s changing something to make it fit better or mending a little hole rather than discarding it just to keep that piece of cloth going. Because one thing I learned through the making of the dress was just how precious cloth has been for most of our history. It’s really such a time consuming and valuable thing. And I just think our current relationship with textiles and clothing has become so disembodied with these huge global supply chains that it’s very easy to start thinking of cloth as something that’s cheap and disposable, which it clearly isn’t, that there’s a huge environmental cost connected with every bit of clothing that been made and also what the clothing is made from.

So just like having an allotment, it may just be a symbolic amount of food that you’re actually growing, but what that connection to the earth and to the ground and your immediate environment? What that gives you is so much bigger than the actual vegetable itself. And I really feel that with cloth and textiles, too. It’s like by just putting some of your own personality into it. Whether it’s just a mend or keeping a piece of clothing going for a little bit longer or deconstructing it, I think that sense of connection is going to just give you something so deep and tangible that I think it will affect your relationship to textiles and I think just able to appreciate them, really, for what they are.

Gail: Yeah. And maybe give us all a sense of our individual responsibilities.

Allan: Yeah. And also individual personality. I think there’s a fear that maybe as we move into a more low carbon future, textiles are going to become how we produce textiles is probably going to change quite radically. I mean, the whole Fibreshed movement again, seems to be tapping into this idea of much more localized cloth production. And I think there’s a fear that maybe we’ll all end up looking like 17th century peasants or something, but I don’t think it will go that way.

I think the more input, more personal input you have into your clothes and cloth, the more individual it becomes. And I think having fashion dictated to us is really largely just a very sort of blunt marketing tool, I think. I don’t think we should be disposing of cloth just because it’s not the most up to date trend. I think leaning into the quality of the cloth and how long you can keep it going and the ways in which you can personalize it, I think those are the real joys to be had from it, rather than just that short hit of something that’s new and then soon forgotten.

Gail: Yeah. No, absolutely. So what happens next, Alan? I mean, obviously I know that you've got the film launching, but do you have other things that you're thinking about moving on to?

Allan: Yes. I mean, soon after I finished making the dress, I made myself a shirt, which I wear to screenings, and that was made from some of the nettle that wasn’t used in the dress flax that I’ve grown and processed and spun over those seven years, too. And bits of hemp that friends of mine have grown. The Contemporary Hempery are doing wonderful things.

Gail: What a wonderful name.

Allan: Yeah, they’re brilliant. The nettle dress, I didn’t dye because I really wanted to just see how the natural colour changed over time. So the dress itself is a sort of living experiment. But the shirt I did dye, used natural dyes. And, yeah, that was a real thrill to actually be able to wear something that I’d made. And likewise, all the whilst I was doing the nettles and stuff, I was spinning wool and other fibres from local farmers where I got fleeces from. So on the loom, at the moment, I’m putting a naturally dyed wool warp on and I’m going to weave that into the next bit of cloth. And I’m still spinning nettle.

I feel my spinning is improving all the time and I think the next nettle garment that I make, probably in many years time, I think will be a lot finer. So I’m really interested in just how far I can push it, how fine a cloth can I make from nettle. And, yeah, there’s just so much to learn. I mean, I’d love to learn more about sewing and pattern cutting and fitting cloth, but all the while, I think that the main thing that keeps me going is just how local I can be in producing cloth. And it’s a much slower way of working. It’s not really a way of working where I can produce stuff to sell, although I do get invited to teach workshops and do talks and that kind of thing. But, yeah, I think there’s just so many avenues and areas in the broad banner of textiles that I love to go into that I think I’m going to be busy and learning right until the end of my days.

Gail: So if somebody else, if somebody listening to this, wants to get involved with nettles and the dyeing and weaving of them and what have you, where would you suggest they think?

Allan: I mean, what I found so awesome was just discovering that, wow, there’s spinning groups in Brighton. Wow, there’s a guild here that has and I think largely that really sustained me and made me love the whole textile area, because unlike so many areas in life, I just found the textile community just couldn’t bend over backwards far enough to share knowledge and skills. And there was always someone on hand to help me. And I really love that free flow of knowledge and information.

I feel like the future is us working together, not against each other. So I’d say definitely look around, see what’s on your doorsteps. There’s bound to be groups doing mending and knitting groups and yeah, whichever area you’ll get into, there’ll be people there who would love to welcome you in. If people want to follow my work, I’m hedgerow couture on social media, on Instagram and Facebook, and if anyone would like to come and see the film, I’d recommend they go to Nettledress.org, which is the website which has all the current list of screenings happening around the country. And on Instagram, it’s nettle dress films. And of course, if it’s nettles in particular, check out the nettle for textiles, the video, the original short film, the website under the same name and the Facebook group under the same name. There’s a bunch of people there who would love to help you and answer your questions.

Gail: Wonderful. And, of course, we'll put on as many links as we can for people in the text for the podcast episode, too.

Allan: Wonderful. Thank you so much.

Gail: Allan, it's been an absolute pleasure speaking to you. Thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day to record this episode. It's very much appreciated.

Allan: Oh, not a problem at all. Thank you so much for having me on. I’ve loved chatting to you. And yeah, onwards and upwards, Jam.

Find Out More

The Nettle Dress is available to watch in selected cinemas.

Follow @nettledressfilm and find Allan Brown on Instagram or on Facebook.