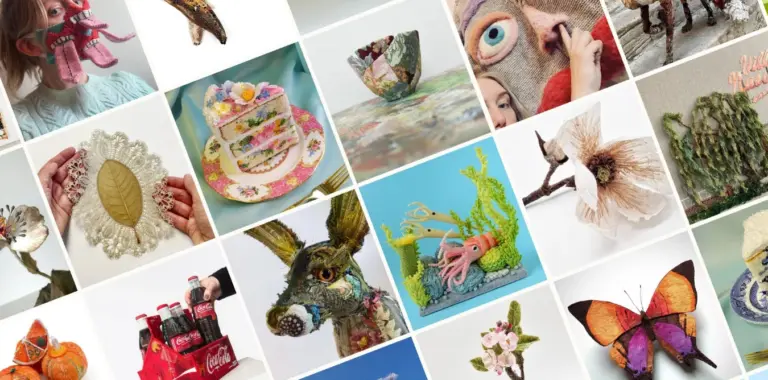

Born into a family of needle workers, Caroline Hyde-Brown’s passion for textiles was ignited at a young age and her journey is a testament to the transformative power of creativity and connection. Initially trained in Fashion Design, Caroline found her true passion in the intricate world of Textile Design and Embroidery, where she discovered the profound significance of working intimately with materials.

Guided by an innate sense of curiosity and an unwavering commitment to her craft, she honed her skills through experimentation and dedication, allowing her artistic voice to blossom organically. Drawing inspiration from the world around her, she weaves together elements of nature, memory, and emotion into intricate pieces of visual storytelling.

Exploring traditional techniques such as hand embroidery, knit, and weave, Caroline’s work serves as a fusion of heritage and innovation, often exploring themes of identity, emotional response, and the ever-evolving landscape of influence.

Caroline’s artistic odyssey has seen her fabrics showcased internationally, with collaborations spanning esteemed brands like Liberty and John Lewis. A pivotal commission from Takashimaya in Japan not only broadened her artistic horizons but also deepened her exploration of Japanese art forms such as Hapa-Zome and Ikebana, as well as the timeless aesthetic philosophy of Wabi Sabi.

Embracing an ethos of global responsibility and collaboration, Caroline’s work delves into the delicate balance between nature and humanity, with a focus on extracting natural colours from flowers, herbs, and weeds, symbolising transience and fragility. Her commitment to sustainability extends to her ongoing research into biomaterials, as she pursues a Masters Degree and collaborates with institutions like the John Innes Centre to explore innovative uses for ancient crops like the Grass Pea.

Throughout her journey, Caroline remains steadfast in her advocacy for honouring traditional handcrafted possessions, recognizing their intrinsic value in a world often overshadowed by mass production. Her art is not merely a reflection of her creativity, but a celebration of heritage, collaboration, and the enduring beauty of the handmade.

“I felt that my creative practice was soaked in overproduction and consumerism, so during my travels along the East and West Coast of Japan I met with a natural dye sensei master who taught me how to extract dyes from flowers and petals as well as Bengala earth- based dye methods. I immersed myself in their culture of honour and tradition and relearnt how to appreciate a slower more thoughtful pace of making.”

Tell us about the piece you’re currently working on.

My current work is themed around grief and memory as well as ‘control’. My father passed away in February and I am also caring for my terminally ill mother. I am carrying out ‘root studies’ of pot bound sown seeds in recycled plastic food packaging as well as homemade moulds of faces, where I have grown seeds that have then been turned upside down and smothered.

The consequent faces are thought provoking and somewhat macabre.

I am travelling between Norfolk and Hampshire. The weeks are passing me by, in a haze of anticipatory grief and time constraints. I also feel very guilty for being absent from my own family back in Norfolk.

This year, however, has also been a pivotal one work wise. Search Press published my first educational book, Forage and Stitch which was the culmination of a three-year writing project looking back at how I have used a combination of plant material, my own foraging practice as well as wellbeing and nature as my own nurturing space.

I was also successful in securing funding for a research project entitled WASTE NOT, investigating natural dyes for the Fashion & Textile Industry. This was on behalf of the UAL, FTTI, London and The British Council. This international collaboration took place between March and August, 2023 and I was primarily based at my home studio in the UK.

My collaborator, Ummi Junid, from Dunia Motif is a batik artist and natural dyer from Malaysia. We explored four different food waste streams and facilitated educational outreach workshops in both the UK and Malaysia as well as Langkawi Island.

What was your first memory of stitching – who taught you?

My first memory of stitching was cross stitch at home, from a pack that my mother had bought me. Both my grandmothers were needlewomen. On my fathers’ side my grandmother was an experienced tapestry embroiderer and my mothers’ mother was a lacemaker, spinner, weaver and embroiderer. All the family clothes were handmade, and I still have my grandmothers silver thimble, scissors and a flower press from my seventh birthday.

My childhood was full of play, crafting and drawing. I spent most of the summer school holidays outside in our large wild garden. At my primary school there was a needlework teacher called Mrs Poole, and she encouraged us all to sew and weave. I carried this on at secondary school where I took a GCSE in Creative Needlework which was only available for a couple of years before the Government decided to scrap it. My A Level Art was fairly traditional, but I also took a GCSE in Fashion Design in which I really enjoyed and achieved good marks for.

My BTEC in Fashion Design, 1990-1992, followed at Solent University in Southampton and after a short time working in London for Gable Clothing Design Company, who were based in Camden, I decided to move to Nottingham to study for a degree in Textile Design. It was here that I specialised in embroidery, and I learnt to apply the fundamentals of textile design practice.

As someone who has a degree in Embroidery, how much of your current success do you attribute to your training. How much did it add to the artist you are today?

I do feel that my time spent developing my creative practice at Nottingham & Trent University and using this particular design course to specialise in embroidery, set me on the path to gaining the experience needed to take part in live projects, competitions as well as seizing other opportunities to visit fashion and textiles events both in the UK and overseas. I can remember travelling to Paris for one pound from tokens that I had collected from the Daily Mail. I had very little money and became incredibly resourceful at visiting Pizza Hut, to eat free pizza with their Book It Reading Club!

During this time there was no internet, so I spent most of my time in the university studios either drawing & painting or reading in the library. We were given free rein to use the Jacquard looms, investigating complex patterns such as brocade, damask and matelassé. I particularly enjoyed the Cornely, a chain stitch embroidery machine, and the vintage Brother knitting machines. I gained a confidence in investigating the fundamental principles of colour, form, scale and pattern and the course had excellent links with industry names such as Michael Brennand-Wood and Jean Draper who was National Chairman of the Embroiderers Guild at that time.

Working for Liberty and John Lewis must have been interesting – did you enjoy your time with them and what prompted you to move on?

After I finished my degree, I must admit to feeling a little overwhelmed. I certainly did not have a master plan. The mid-nineties I remember as a time when the rise of the internet was ushering in a radical new era of communication, business and entertainment. I had very little money, so I moved back to Southampton for an office job, but during late 1995, I decided to attend a funded workshop from the Arts Council in Winchester, with the late Dr Janet Summerton. She played a pivotal role in my decision to become a freelancer, and I still have the workshop booklet that she encouraged us to complete. My successful funding application in 2021 with the DYCP Arts Council, I still attributed to her over twenty-five years later.

After this workshop I wrote to Liberty in Regent Street and after a meeting with their Buyer, was invited to work for the British Craft Department. This small craft gallery was an invaluable stepping-stone to a peripatetic lifestyle which involved many tight deadlines. During this time, I was also taking part in Exhibitions throughout the UK with Craft In Focus, Art in Action at Waterperry Gardens, Hampton Court Flower Show and Contemporary Textiles in Teddington.

In 2002 Liberty closed the Bookshop at the store as well as British Crafts, and so it was then I decided to work for John Lewis. I completed three seasons, taking part in a Valentines Story for their Interiors Department as well as providing framed pieces for their flagship store. I learnt how to design embroidered pieces, gaining experience in manufacture and production but I was feeling stifled with over production and making became a habit rather than a beneficial change.

Spending time in Japan clearly had a profound influence on you. How has it impacted your practice?

My contract with Takashimaya happened at the perfect time. I was exhibiting in March 2002, with the Country Living Spring Fair at the Business Design Centre in Islington, London, when I was approached by the International Buyers from Takashimaya, a major department store in Japan. They subsequently invited me out to Japan to take part in their British Craft Promotion at the Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto store.

This immersive experience left an indelible mark on me not just as a person, but also as a craftsperson, a maker and a designer. I studied Ikebana for six weeks using pine, bamboo and cherry blossom and I became very aware of the relationship of my surrounding space and the aesthetic elements of our seasons which I still use in my practice today. Two of the main principles of this ancient art form is minimalism and harmony. I felt that my creative practice was soaked in overproduction and consumerism, so during my travels along the East and West Coast of Japan I met with a natural dye sensei master who taught me how to extract dyes from flowers and petals as well as Bengala earth- based dye methods. I immersed myself in their culture of honour and tradition and relearnt how to appreciate a slower more thoughtful pace of making. Wabi Sabi became an integral part of my own views of transience and imperfection and again I still try to let go of becoming attached to possessions or material things.

You link your embroidery to your garden via extraction of natural colour from plants you grow. Can you suggest ways or processes whereby our students could begin to do the same?

My creative process is closely intertwined with the four seasons. My natural dyeing process from late Autumn to early Summer (October to April) lies dormant but I use this time to stock up on windfallen twigs, bark, berries and leaves. The cold damp weather is not good for drying outside but once the sunlight is stronger and there is some warmth on my garden tables, I usually start again. I use most of my fresh flowers such as dahlias, rose petals, grasses, hollyhocks, delphiniums, marigold or golden rod as well as foraging for anything that I feel might make a nice dye colour. I have two induction hobs in my studio which are invaluable as well as some large dyepots. I harvest rainwater with a waterbutt and buckets and the solar heat provides me with plenty of opportunity to do some solar dyeing.

My meadow garden is where I am currently researching tannin rich wild weeds such as herb robert, nettle, comfrey, plantain and mallow. Other plants such as weld, dyers broom, tansy, lady’s bedstraw are dried in a large herbal drying stack hanging in my studio which works well in the warmer sunshine.

I am also experimenting with different barks of shrubs and trees, such as cherry, fruit trees, oak, hazel, birch, mulberry and beech and walnut husks. I gather oak galls, berries, during the autumn and in the winter, I freeze nettles, blackberries and rose petals. My culinary stove top method is simple and accessible. I bring the rainwater to the boil and then turn it off leaving the plant material to soak from two hours to one week. I use rainwater as it has a slightly higher acidic content with a ph value of 5-5.5, which when mixed with nitrogen from tannin rich plants makes for interesting dye colour combinations.

Foraged Treasures 2023.

What artists inspire you personally?

The work of El Anatsui completely blows me away. His shimmering installation pieces truly reveal how value can be placed into a completely different context of waste utilisation. I would really like to visit his current Exhibition ‘Behind The Red Moon’ at The Tate Modern. I am also inspired by the Japanese weaver Kazahito Takadoi and his intricate use of plant fibres such as bamboo, and twigs as well as

German artist Diane Scherer who creates incredible “root-weavings”.

I came across the work of this textile artist whilst studying for my master’s degree during the pandemic. Scherer makes use of the intricate dynamics of plant root systems in order to create a textile-like material that builds the basis for her final pieces. By blending natural and human-made elements, her work reflects an intimate connection with plants: “It is a collaboration, a combination of my manipulations and their own will’’.

What’s next?

My research into Agri-Textiles is ongoing. For the last four years I have been collaborating with two plant scientists at John Innes Research Centre in Norwich and NIAB in Cambridge. We are studying the residue of a Neolithic crop called grass pea and I am still focusing on paper making processes and how to eventually create some form of yarn or fibre.

I am currently making work for an Exhibition at The Crypt Gallery in Norwich in collaboration with the Norfolk Contemporary Craft Society, as well as three weekends in November at Blackthorpe Barns in Rougham, Suffolk. Their annual Christmas Crafts are a highlight of my calendar as I meet up with other makers that have become friends and I have known for over thirty years.

You can also find me working and exhibiting at my own studio space at Designer Makers 21 Gallery in Diss near to where I live on the Norfolk – Suffolk border.

My next book I hope to publish will be called ‘Unearthed’ – beautiful objects for a climate conscious home. This book centres around six projects that will show you how to create three dimensional objects such as bowls, lampshades, cushions and ornaments from foraged plant fibres and agricultural waste.

Links to further reading:

www.theartofembroidery.co.uk

www.designermakers21.co.uk

www.jic.ac.uk

www.thelivingfieldmagazine.co.uk

Key Takeaways:

1. Personal Inspiration and Themes: Caroline’s work is deeply influenced by personal experiences, including themes of grief, memory, and control. Artists can draw inspiration from their own lives and emotions to create meaningful and thought-provoking pieces.

2. Utilizing Natural Materials: Caroline’s practise involves extracting natural colours from plants grown in her garden, demonstrating how artists can incorporate sustainable and environmentally friendly methods into their work. Experimenting with natural dyes and foraged materials can add depth and authenticity to textile art.

3. Continuous Learning and Development: Caroline’s journey from studying embroidery to exploring natural dyeing techniques exemplifies the importance of ongoing learning and skill development. Artists should embrace opportunities to expand their knowledge and experiment with new techniques to evolve their practice.

4. Cultural Immersion and Influence: Caroline’s experience in Japan profoundly impacted her practice, leading to a deeper appreciation for minimalism, harmony, and traditional craft techniques. Immersing oneself in different cultures can broaden artistic perspectives and inspire new directions in creativity.

5. Collaboration and Research: Collaborating with scientists and researchers has allowed Caroline to explore innovative avenues such as Agri-Textiles, combining art with scientific inquiry. Artists can benefit from interdisciplinary collaborations and research partnerships to push boundaries and discover novel approaches to their work.

6. Exhibition and Publication Opportunities: Participating in exhibitions, craft fairs, and publishing books are essential for showcasing artwork and reaching a wider audience. Artists should actively seek out opportunities to exhibit their work and share their creative journey with others.

7. Environmental Consciousness: Caroline’s focus on creating objects from foraged plant fibers and agricultural waste reflects a commitment to sustainability and environmental consciousness. Artists can align their practice with eco-friendly principles by repurposing materials and minimizing waste in their creative process.