We’re utilising our brand new Podcast channel, Textile Talk, to bring you in depth interviews with inspiring artists. In this latest episode we talk to watercolour artist, Ruth Clayton, who also teaches our drawing course for beginners.

Textile Talk with Ruth Clayton

Listen to the podcast now or read her interview below. Take a look at a small collection of her work and find out more about where and when you can see her work in upcoming shows.

About Ruth Clayton

Ruth qualified as a Graphic Designer at Leeds Metropolitan University, specialising in illustration, in 1986. She then gained a teaching qualification at Manchester University.

She has spent many years as an Art teacher working in high schools and tertiary Colleges. She now shares a studio with her partner Stuart Gray at Farfield Mill in Sedbergh, Cumbria, where they work, teach, and sell their paintings.

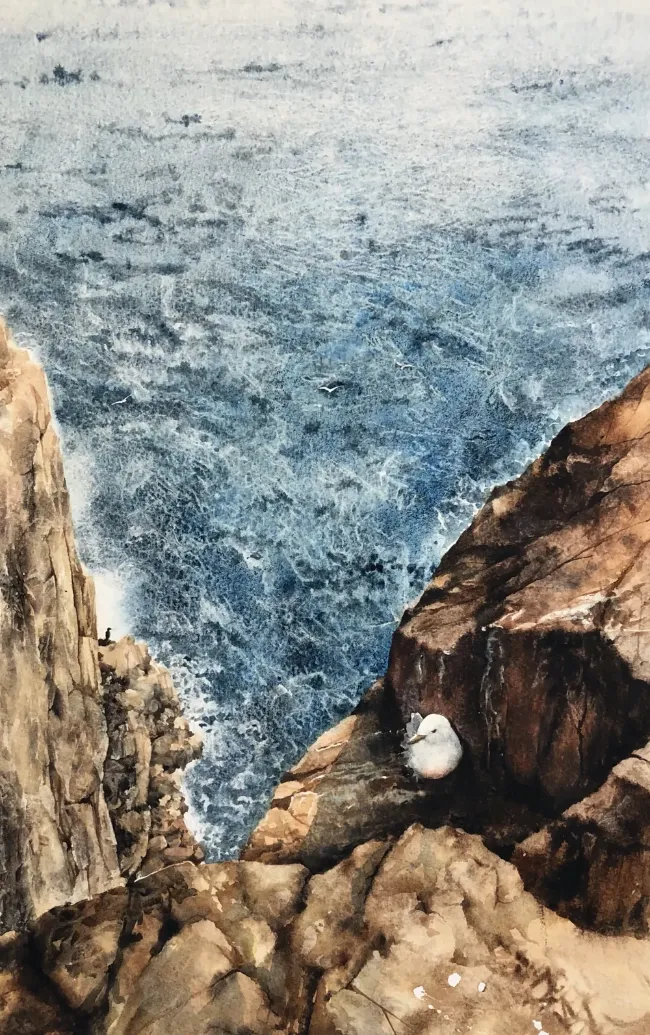

She specialises in watercolour and likes to try and capture the energy of water in all its forms, from crashing waves to babbling brooks and cascading waterfalls. She loves how water reflects the surrounding force of nature with all its colours and intricate patterns. She also loves to paint hedgerows and undergrowth and uses many techniques to achieve the results she wants, ranging from clingfilm to rice!!

“My true passion is painting the Ocean, not in its calm and gentle state but when it appears angry and full of energy. I am memorised when watching the sea and I find it very therapeutic; it grounds me and helps me to see my life in perspective.

I’m very sad at the current state of some of our oceans and I’m extremely concerned about the rising sea levels that we are seeing. This is having a huge impact on our wildlife and our own existence. I hope that I can highlight some of these issues through my artwork and help support the growing charities that are battling to make a difference before it’s too late.” Ruth Clayton

Interview with Ruth Clayton

Gail: Hello, everyone, and a very warm welcome to this Textile Talks podcast. I’m Gail Cowley and I’ll be your host today. Joining me is Ruth Clayton, who’s a wonderful artist that I’ve known for many years. Just to give you a little bit of background on Ruth, she qualified as a graphic designer at Leeds Metropolitan University, specializing in illustration in 1986. She then gained a teaching qualification at Manchester University. She has spent many years as an art teacher working in both high schools and tertiary colleges. She now shares a studio with her partner, Stuart Gray at Farfield Mill in Sebra, Cumbria, where they work, teach and sell their paintings. She specializes in watercolor and likes to try and capture the energy of water in all its forms, from crashing waves to babbling brooks and cascading waterfalls. She enjoys how water reflects the surrounding force of nature and all its colors and intricate patterns. And she also loves to paint hedgerows and undergrowth and uses many techniques to achieve the results she wants, ranging from cling film to Wright.

Gail: Hello, Ruth, and thank you so much for joining us for this podcast today. It’s lovely to have you here. One of the first things that I’d like to ask is if you could introduce us to the techniques and materials that you use in your art.

Ruth: Yes, I can certainly do that because I would class myself as a watercolourist, but probably watercolour with a difference. I wouldn’t call myself a purist. So, for example, a purist would never use white or black, and I do tend to use white. I’ll even use pastel. I will use different inks, usually acrylic inks, which are waterproof. So in a way, it’s probably veering on the mixed medium. But I still class myself as a watercolourist because that’s the medium that I love, I’ve always loved. And I love what the paint does if you allow it time to do its thing. Watercolor, pastel, inks, and sometimes a bit of color pencil as well.

Gail: I’m by no means an expert with any of them, but I’ve always found watercolor to be quite unforgiving. Obviously you don’t take that view.

Ruth: No, I don’t at all. I do think that’s a myth, but I do think you need to know a little bit about the pigment. So, for example, that is true. It isn’t very forgiving if you’re using staining colors, which means if you wanted to get something off your paper, you can’t get it off. But if you use non staining colors, you can very often just wash it right back to the white paper. So it’s far more forgiving than you actually think.

Gail: Is it something that you would recommend somebody as a complete beginner to start with or would you think something else would be more suitable?

Ruth: I think it’s as good as any other medium. I think you know what you know. So if you’re taught how to use acrylic and then you try to use watercolor you’ll find that very different and vice versa. If you get taught to use watercolor and then get taught acrylic, have a go at acrylic, you’ll find that very different. So I do think it’s all in the planning and understanding the paint, understanding the medium. And then to me, it’s no more difficult than anything else.

Gail: Actually, that’s really interesting because I think it’s the planning that on a personal lab, I’ve always had problems with, because you have to work out where your life at, spaces have to be, don’t you? And then either mask off or you sort of work in reverse to the way that you work with many of the mediums.

Ruth: And to me, it’s all in the planning. I think with maybe mediums like acrylic and on oil to a certain extent. And if you’re out there and you’re proficient in those mediums, you might disagree with me, but to a certain extent, you can cover up some of your mistakes. You can put light on dark and so on. You can put fat over thin and all of that, but with watercolor, yes. I would start off by assessing my picture. I’ll look at it and like you said, I will think, well, are there any whites that need to be saved? How am I going to do that? Is that going to be just painting around an area so that you leave the paper shining through if you like? Or am I going to use masking fluid or am I going to lift off? And then that means you need to know a little bit about, as I mentioned before, about whether your colors are staining or not. So I go through a process. I call it the P process plan, experiment and Apply. And I do a sheet. I do a sheet of all the colors that I’m going to use. I’ll mix all the colors, get the colors I want, and then I will actually see if they lift. And then I’ll label them all. So I go through that. Even though I’ve been painted for many years, I never miss that stage out.

Gail: And by lifting off, you mean sort of removing with a dry tissue?

Ruth: Well, no, with a damp brush, really. You just get a damp brush and you just go over the paint gently so you’re not fluffing the paper up, but you’re literally just sort of moving the paint. And when it begins to move, you can then get a tissue and just take off any surplus paint.

Gail: Yeah, it’s that planning process that I feel a little bit overwhelmed by. When I think about water colors, I think acrylics, I feel a little bit more because, as you say, you can paint over, so if you make a mistake, you just go over it. But that planning process is interesting because it’s what we always encourage our students to do, which is really think about something before you’re going to do it. Put it down. So it’s not quite as immediate as I think. Often people think it might be, not at all.

Ruth: And a lot of people will think, oh, you can’t be bothered. But to be honest, you’ll save yourself a lot of time and a lot of materials because you can waste an awful lot of paint by making mistakes washing it off. Whereas if you just do that planning process first, any mistakes you’re going to make, you’re going to make in that time, in that process, so that when you come to do your final piece, you pretty much know what you’re doing. You know your color palette, you know what colors will lift, you know what techniques you’re going to use. You’ve tried them all out on a sheet beforehand.

Gail: Yes. So you’re obviously fully organized before you start to paint, rather than as perhaps I have done during.

Ruth: Definitely, yes. So many people just jump in, even when I’m teaching. Sometimes I will. It’s all step by step, and they’ll say, right, mix your colors first, test your colors. I’ll come round and your colors have got to match mine. And then there’s still the odd person who’s romping ahead and not mixing the colors, and they always get into difficulty.

Gail: I know that you did start your career as an art teacher, didn’t you?

Ruth: I did.

Gail: I mean, that must have been really interesting. But then, of course, you made a transition to working as a full time artist. You tell me a little bit about how that came about.

Ruth: Yeah, I’ve worked in high school for a number of years, and I ended up at Bolton School in the girls division as a permanent part timer. And my hours really depended. There were two other members of staff in the department and dependent upon how many girls would opt for art in year ten and eleven would depend on how many hours I got, so they would obviously have to fill their timetable, and I got basically what was left. So every year it changed. And there was one year, really, where I wasn’t getting as many hours. So that’s when I set up a small gallery in Cedar Farm Galleries, actually, in Maudsley.

I set up a studio space there and started to teach adults. So I was teaching high school children for part of the week, and I was teaching adults for the rest of the week. But then eventually the year after that, I got more hours at Bolton. It all became a little bit undoable. Well, undoable, if you know what I mean. It’s a such a word. It became very difficult. And the two jobs together were more than a full time job.

I had a decision to make, and I made it in that if there are any teachers out there, you’ll know that that term between October and Christmas is really hard in our school. All our parents evenings were then you’re getting up in the dark, you’re coming home in the dark. And that’s when I just thought, I can’t keep doing this. I made a decision that I had to choose one or the other, so I opted to leave full time teaching at the high school and to concentrate more in the studio. And then I was selling work alongside teaching the adults. It was still a bit of both. And then I just decided that I would change the balance and try and do more painting for me, to see if I could walk the walk. And teaching became a little bit more of a backstage thing, really. That’s how it happened. It was just a natural process.

Gail: That must have been quite a change from going from teaching high school to teaching adults. I would imagine all of that, the approaches between those two different age groups must have been really marked. Am I right?

Ruth: Absolutely right. Yes. It’s so different. I mean, there’s pros and cons with both, I would say. I love to teach in the children, don’t get me wrong, and that’s not why I left, but to a certain extent, you could tell them what they should be doing, and if they were misbehaving, you could even sell them out. You can’t do that with an adult, or if you can, they won’t be coming back the week after. The odd occasion when I thought, yeah, with my teacher hat on here, they would be sent to the head now for a good talking to.

Gail: Absolutely.

Ruth: But then adults, they’re always so keen and so willing to learn because they’re paying to come. So, yeah, very different. Very different. But I love them both.

Gail: Most of our students, of course, are adults. We do get the odd one that’s a bit younger, but in general, they’re adults. Do you find that they come with all their own hang ups? Because certainly we get lots of people that say, I couldn’t possibly draw, I couldn’t possibly paint, I can’t do any sort of art.

Ruth: Yes, absolutely. If I had a pound for every time somebody has said, oh, I can’t draw, I’d be a very rich lady. But it’s not about that. I’ve spent many, many years defending my subject, for one point, really, because sometimes when you’re an artist, people don’t think that that’s a proper job, but also, people seem to think that to be good at art, you have to be able to draw. And you will know as well as I do that that’s not true. You could have a fantastic concept of color or pattern or design, but it seems to be, yeah, I can’t draw. I was told at school that I was rubbish. I’ve heard that so many times. Art teachers out there have got a lot to answer for. In actual fact, I lost my confidence years ago because somebody told me that I was rubbish and don’t give up the day job, sort of thing.

Gail: So, yeah, confidence is really a lot of it, isn’t it? It’s giving them that confidence that they can do it. I think if you can overcome that with somebody, then you’re most of the way there, I think, yeah.

Ruth: And to be honest, it’s with children as well. Because this is quite interesting, is that at year seven I had taught primary as well because I’d been asked to go into primary schools and teach young kids on occasions. And nearly all young children, maybe with the exception of year six. You know, if you ask them who thinks here they’re good at art, I would say 90%. If not, 99 or 100% would put the hand up. But when you get those children at year seven, at high school, if you ask them the same question, you’d be very surprised that very few will put their hand up.

Gail: What happens in between those years to make them feel that way? I mean, did you ever come to any sort of conclusions to what that might be?

Ruth: I think a lot of it is peer pressure. I think all of a sudden, they are looking at what their friends are doing, once again, what teachers say to you, building your confidence. But I suppose it would be a good thing to do for a masters, for example, to try and find that out. But no, I just think it’s to do with the age, to get into that age where they really are bothered what people think about them.

Gail: Very self conscious.

Ruth: Yeah, incredibly. And in fact, the very first project that I would do with the year sevens, I would ask that question and we would have a chat about it, and then I would say, right, okay, we’re all going to do this now, and everybody will be able to do it. There won’t be anybody who’s better than somebody else. And we would design our own Kandinsky for silly.

Kandinsky was an abstract artist, so they would put a little still life set up. It could even be like the contents of their pencil case. And I’d say, Right, we’re going to draw that now. And you’d see absolute dread on the faces of some of the kids. But then I would say, right, but you’re not going to look at what you’re drawing, so you’re going to be looking at your still life and you’re going to be drawing to the side or just behind you with your pen, and you’re not allowed to cheat. So it became really funny. It was good fun.

I would go around and I’d be checking that nobody was cheating and we’d have a bit of a laugh. And then at the end, obviously, you can imagine the sort of design that they would get, particularly when you want to take your pencil off the paper and put it down somewhere else and you’re not allowed to look at your paper. But what they did get was this beautiful, free, abstract image, which we then worked on. We thickened some of the lines, we added colour, and then basically they came up with their own Kandinsky design. And that was always a turning point for the children because it all felt like they were on a level playing field, really.

Gail: Yeah, I’m sure. I suppose a lot of it depends on who it is that teaches you art and if they can draw something out of you that perhaps you don’t see in yourself.

Ruth: Yeah, it is, it’s sort of homing in on what that child is interested in, or that adult. And by the way, that Kandinsky project is on my YouTube channel, if anybody wanted to have a go at that. But it is like the child who is really switched off from everything. If you can find something that they are interested in, whether that’s motorbikes or whether it’s fashion or whatever, and sort of go down that route and try and find something quite arty that’s attached to that, then you’ll build their confidence because they’re interested then. And it’s the same with adults, I think.

Gail: No, I’m sure you’re right. So, I mean, you obviously made that change from teaching at high school to teaching adults. Now, it’s been a little bit different again, because it’s been sort of very much about the gallery. Can you tell us a little bit about what you do at Wicker Fish Gallery?

Ruth: Yeah. Now, the word wicker fish, I’ll tell you about that first, and I am moving away from that name a little bit, but just to tell you how that cropped up in the first place, just mentioning Cedar Farm Galleries again, I was there with my youngest daughter, and she’s what, nearly 30 now, so she was about nine. And we’d gone because they were doing a little workshop for children making Wicker animals, and Beth made a Wicker Fish and we went for lunch afterwards and she was always good company and she was saying, I think you should have a studio somewhere. And we talked about it and then she said, Why don’t you have one here? And I’d never really thought about approaching them at Cedar Farm to see if there were any free studios. And that sort of prompted me to go and ask the owners.

As it happened, the timing was perfect because they were just converting a new outbuilding called the Pig Barn into four new studios. And Peter, who ran Cedar Farmy, it was never first come, first served. He didn’t look at what he thought would fit into the whole ethos of the place. And I was fortunate enough to be put on a waiting list there. So I did say to my youngest daughter, if ever that comes off, then we’ll call it the Wickerfish, because it was after having our little conversation, and it’s been the Wicker Fish for years. And my partner, now, he is part of that, he’s also an artist, but I’ve found that the two of us are really beginning to sort of separate a little bit because his work is very different to mine. And I tend to sort of work under the name of Ruth Clayton Artist now, but the gallery itself is still called a Wicker Fish.

So the physical gallery that people can come and visit is still called the Wicker Fish because there’s Stuart’s work in there and mine. But then you’ll notice in there that they have got my business cards which say Ruth Clayton Artist and Stewart’s business cards which are different.

Gail: It’s a really unusual name, isn’t it? Certainly one that sticks in the mind, I think.

Ruth: Yeah, it was just because of that day really was a big turning point for me. And then it wasn’t long after that that I left teaching in high school. I’m not quite ready to shed that name because I’m emotionally attached to it. But at some point I probably will just have started to rebrand, really, with Ruth Clayton Artist. All my social media platforms are in that name. We do have a Wicker Fish website, but I haven’t been on there for quite some time.

Gail: I was actually on there the other day because I had a good laugh at the video that you and Stuart have done. If the listeners get a chance to go on and have a look at.

Ruth: It, it’s great to do with the cake.

Gail: The speed is at one. Yes.

Ruth: Okay.

Gail: That was great fun. I thought that was smashing.

Ruth: Thank you. Yeah, I do think these little videos, even on Instagram and doing reels and things, is quite good once you get into how to do them and how to record them. And I’ve taught myself how to use Imovie and I put little movies together and it speaks volumes, really, doesn’t it? A little video?

Gail: It does. It actually tells you a lot about the person as well. Certainly says that they have a good sense of humor when I watch that one, but it does tell you something about them. And I think when you buy a painting, an original, you’re almost buying into that person, really, aren’t you? It’s a little bit of them, in a way that you’re purchasing that sounds a bit strange, but no, you are right.

Ruth: And so many people have said this. When you are looking at your marketing, that word branding always comes up. And I think, here we go again. But it’s very true, because if you have like a brand about what you do, people want to get involved in that. They want to know more about you and your life and how you go about it and what your studio looks like. So, yeah, you are right with that. Absolutely.

Gail: Sounds strange. How do you deal with the fame? Do you welcome people that are sort of wanting to know more about you?

Ruth: Yeah, well, I don’t have many followers on Instagram at all, and that’s something that’s another issue, really. I think that’s really difficult. More and more so these days. But I do have I mean, yeah, I call them my groupies, which they’ve almost become friends because we still do little bits of teaching up here and people travel quite a long way to come and people do like my work and not everybody, but you have a following and it’s nice. It’s not massive. I don’t want it to be massive. I’m quite happy with the way it is, to be honest. I haven’t gotten educated about it.

Gail: I’m sure it must take a huge amount of self discipline to keep on producing work for sale because we tend to think of art or I tend to think of art. I know certainly students do. It’s something that the artistic muse strikes and you just have to sit down and patience, very immediate thing. But of course, if you’re doing it for a living, for a job, an occupation, then you’re going to have to do that on a fairly regular basis. How do you manage that whole creative process that you have to go through in order to keep pictures on the walls that people can buy with quite.

Ruth: A bit of organization, really, I would say with my Bible, which is my old filefax that my mom and dad bought me when I was 40. I’ve tried to sort of use the online calendars and things, but I can’t get on with them really to the same degree because I can’t see everything just there when I want it. And because throughout the year I work towards certain open art exhibitions, certain galleries take my work and I have been caught out in the past because, for example, a particular exhibition, you’d know, would be starting in July. But then on the occasions I’ve forgotten that actually they want the work three weeks before that, which means then you have to have them ready. So you have to start painting that picture or whatever.

Well, before that. And that has caught me on the hop on many occasions. So I do have everything written down. Like I have a desk diary and like a year at a glance. And I will put in all the deadlines of when work has got to be started, when work has got to be submitted, and if you’re successful, when has it got to be delivered? If you’re not successful, when did you have to pick it up? There’s all those different dates around one event. So that’s how I do it. And really another thing that I used to trip myself up with all the time is I’d see something in my diary and think, oh yeah, I’ve got such a thing on. And then somebody would ask me, couldn’t you come and do a demonstration, an art society? And I’d look and I’d see it was free, but then I’d not look at the days before or the days after. So all of a sudden I’d find that I’d be running around trying to fit everything in because I’ve got one thing after the other after the other, with no breathing space in between. I don’t do that anymore. I do look at my diary and think, well, actually I could do is give myself a couple of days after that before I do anything else. But it’s quite a lot of planning.

And in January we tend to do that because just at the moment, I’m not working on anything and this is the time that I do prepare, that I think about what I want to apply for, for next year. And then I’ll get a new diary, I’ll get my new little things, inserts for the file facts, and then I’ll start to fill them in and then you can see it all. And that’s the only way that I can keep myself on track, really. And at the moment you would laugh in the studio because I have nothing on the wall and I’ve just got a notice saying, oops, there doesn’t seem to be an awful lot of work here. A lot of it is up at St ABB’s Gallery, at a lovely little gallery called Number Four.

And I have a little exhibition downstairs, actually. So upstairs in my gallery, there’s nothing on the wall, but if you go downstairs to the floor level two, there’s a little mini exhibition of mine. So there is work in the building. But no, sometimes I just can’t paint fast enough because I work big as well and yeah, so it’s always a challenge.

Gail: Do you feel the pressure? Because there is a pressure if you know that you’ve got an exhibition book or there’s a pressure to produce, did you find that actually inhibits your work?

Ruth: Yes and no. If I’m organized and I start well in advance, then I’m fine. And it’s not normally the work that will give me the pressure. It will be all the admin, it’ll be the paperwork. Some of these galleries, they’ll want you to do an artist statement or they’ll want you to do X, Y and Z, and they’ll want you to send images and they’ll want you to send it at a certain resolution and that can promote a bit of pressure. But the actual painting itself, no, I’m in my happy place there, as long as I give myself enough time.

Gail: Yes, I suppose it’s lovely that you can still say that. Sometimes when we do something on a very regular basis, we can get fed up, can’t we?

Ruth: Yeah. No, I don’t think I’ll ever get fed up when people say this. It sounds I don’t know, it sounds a bit woo woo when you say it’s part of who I am, but it really is. I can’t ever imagine not painting. And if I’m not painting, I’m knitting. If I’m not knitting, I’m needle felting. If I’m not needle felting, I’m doing something else. Because creativity is such a huge part of my life. So in Lockdown I was never bored because I’d got a whole host of things that I’ve been wanting to do and I had the opportunity yes, I.

Gail: Think for a lot of creative people it was catch up time during Lockdown, wasn’t it?

Ruth: Yeah, because I’ve always wanted to write a book and I was writing a children’s book and I started doing some illustrations for that. I’ve written the book, but I’ve lost the book at the moment. It’s somewhere in the house. So it just gave me the opportunity because I am a trained illustrator but I don’t do much illustration now I work much bigger and much freer and I think one of the reasons for that is that my eyesight is not what it used to be. Now I wear very focals. I think that very close work is quite tricky, so I have developed this much bigger freer style because of that.

Gail: So what would a typical day look like for you? I mean, do you start to paint the moment you get up or do you interperse it with other things? How would that look for you?

Ruth: Well, I don’t often paint that home. I try to keep that very separate. I keep my home my home. I only live in a little house and I’m not the tidiest of person when I’m working, I always clear up at the end before I start a new project. But while I’m working, I am quite messy and I don’t like to be surrounded by mess, it gets on my nerves, so I do keep it separate so it’s working at the gallery. So a typical day will be not getting up at a ridiculous time. I tend to sort of get little jobs done and I might get to the studio for about half ten because that’s usually when it’s far. Field Mill, where I have my studio in Sedva, and it opens at 10:30, so I usually wander around between ten and half past and then, yeah, I will pretty much start painting straight away, depending upon who’s in there and how much chattering I’m doing and how many coffees I go for. But we tend to knock off about 04:00 ish. But I’m not in every day, probably three, four times a week. The rest of the week I might be trying to catch up with marketing or other jobs. Really?

Gail: I presume that you’ll produce some pieces to sell but then perhaps you’ll have a commission from somebody. Do you prefer one or the other?

Ruth: I don’t work for commissions at all anymore. I’ve had many, many years of doing that and I hate it.

Gail: That’s fairly strong.

Ruth: They are. That’s honest, isn’t it? It just inhibits what I do. I don’t know, it’s really strange, something switches in my head. You look at that piece of paper and then if it’s just a painting that I have this fancy doing, it’ll flow as soon.

As I know that I’ve got to do a painting for somebody and they know what they want to see immediately I’ve got a block I’m inhibited from. That doesn’t mean to say I haven’t done commissions, I’ve done hundreds of commissions, but I don’t enjoy them. And I pretty much got to that stage. I thought, I’m getting too old now to be doing things I don’t want to do and I don’t enjoy doing. So I do a painting and if somebody likes it, they’ll buy it.

Gail: Yeah, I can understand that because in a way, you’re painting something through someone else’s eyes almost, aren’t you? Which is hard, it’s hard to second guess what someone else might want.

Ruth: It is. I mean, I have done them and there are some that I do enjoy, but I’ve had some horrors, really, and I’m not going to tell you them now because it’s quite old person might be listening or those people might be listening.

I’ve got a couple just would make you howl some of the things that people have asked you to do, and even like portraits, which I used to do years ago, they give you like a four by three inch picture with like, the child would have red eye. And I think, I’m a painter, I’m not a magician. So it’s I have you know, people do expect an awful lot, and I’ve never had anybody who’s not happy with the commission, but it’s really quite a recent thing, I would say this last year, year and a half, I thought, well, let’s put it this way. I’m not going to advertise that. I do commissions if somebody asks me, somebody I know. And I think, yeah, I wouldn’t mind doing that, then that’s a different thing. But if I don’t advertise it at.

Gail: All yeah, yeah, no, I can understand. I mean, how much obviously, I suppose when it all comes to the end of it, it’s great to enjoy what you do. That’s wonderful. But at the end of it, it has to have a price tag put on it, it’s going to be sold and we all have to eat, don’t we? So how do you work out, Ruth, how much to charge for something? I know this is something that our students tend to struggle with. They do something, they perhaps they knit something, they owe something, and then they find it really hard to know how to pass on the cost of their labor. Can you give us any insight about how you tackle that?

Ruth: I will say it’s incredibly hard. It’s really difficult. I think it depends on the sort of person you are as well. I could sell somebody else’s work better than I could sell my own, and there’s all sorts of different ways of doing it and for years people used to say, oh, you’re not charging enough, but then I used to come up with things. This is the one I was living near chorley. I would say this is Chorley, not Chelsea. And I do think there is an element of that. I think it depends where you are and where you’re selling your work as to what sort of people are going to be coming and looking at that. But then I did have to come up with a way of working it out. So I do it by square inch, really. I measure the length by the width, and then you can times that by 1.5, or you can just do it by one or whatever, but that would give me a starting point, and then I can look then you can add the cost of your frame and all the rest of it. But then I would look at that piece of work and think, does it appear to be worth that or not? For example, if I use a big A one frame, but I’ve done a painting that pretty much is all in the center and it bleeds out almost like a vignette, then in a way, you could say, well, it isn’t an A one painting.

It’s probably an A two painting with a lot of air around it and a lot of space. So I would actually just measure the actual artwork bit. So I’d measure the A two bit and I would then put it in an A one frame. But that gives you somewhere to start. Lots of people do it in different ways, but that’s been pretty good for Stuart and I. It does. It gives you a baseline and then you can think, no, I think it’s worth more than that. Or actually, I think I should just bring it down a little bit. And then, of course, you’ve got to think about commission on top of that, which is a big headache for people selling in galleries, even in our gallery here. I mean, Farfield Mill has lots of other art studios, and if I’m in there, then I can sell direct. But if I’m not in there and somebody comes along and buys a piece of work and takes it to reception, then they obviously will have a commission.

Gail: Yes.

Ruth: So you have to work that out. So once you put your commission on, then look at it and think, oh gosh, that’s getting a bit too expensive. Have I got any leeway? And to me, that’s the way I do it. I’m not saying it’s the perfect way.

Gail: I think it’s finding something that works for you, isn’t it? If it works generally, as a rule, then that’s got to be useful.

Ruth: Yes, I would say so.

Gail: Commission is one of those controversial things, isn’t it? Because obviously all galleries will charge. I’ll put a different rate of commission on, and I think we’ve all been there when someone there’s been a gallery opening, maybe an opening night or something like that, you can hear people going around and saying, well, I won’t bite in here. I won’t pay that commission. I’ll go straight to the artist and see if I can get it cheaper.

Ruth: Yet you do get that. And there’s nothing that annoys me more, really, about people trying to barter as well. I’ve had that people do approach the artist direct, and then that means the gallery misses out, really. But having said that, if they’ve got a piece of artwork in there, I think as an artist, I would say, well, if you want it, you’ll have to buy it from the gallery. But if it comes back to me at the end of the exhibition and I still have it and it hasn’t been sold, then maybe we can have a conversation.

Gail: Yeah, that’s different.

Ruth: That is different. But I remember a few times where there was this one chap I remember in particular, once they were aware, and he kept coming, looking at this particular piece of work, and he kept saying, what’s your best price? And I wouldn’t budge. And I kept saying, well, no, that is the price, okay, because there’s somebody on the other side over there, and I really like his work as well, and I can’t make my mind up. And I thought, no, I’ve got to stick to my guns here. So I said, Well, I can’t help you with that. And it kept coming round, and I became quite irritated because you wouldn’t bother with a solicitor or an electrician or people feel that they can do that. Anyway, just to sort of tell you how the story ended, I stood by the guns, and then I was beginning to weaken because it was getting nearer to the end of the day, and I thought, oh, maybe I should have done that. At least I don’t have a sale. When this really lovely gentleman arrived, and he just looked at it just for a few minutes, and he said, I’ll have that. He said to me it was a personal thing for him. I, once again, I want to say exactly, because he’d written a poem basically years ago, and he wanted a painting to actually depict his poem, and he’d been looking for a long time, and my picture satisfied that need for him. And I thought, oh, I’m so glad that you’ve got it. And then he sent me a lovely photograph of it in situ above the fireplace. So, yeah, I do think we have to stick to our guns, really, because another way of pricing your work is the amount of time it’s taking you, particularly with textiles, the hours. I’ve got a very good friend who’s an embroiderer hours and hours and hours, and she probably doesn’t get a good hourly rate at all.

Gail: It’s very difficult to actually price your work. I think sometimes people that I’ve known have found a way around actually selling the originals. They’ll photograph something really well and maybe make cards out of it and that kind of thing. So there are ways of offsetting some of the costs, but, yes, it certainly is quite a time consuming thing to do. But, of course, so is what you do. I suppose they must feel like, well, not quite your children, but you must like to see them go to a good home, I imagine.

Ruth: Yeah, I do. And when somebody comes and say, oh, I love your work, and yeah, you do get quite a buzz from that, I don’t mind letting them go, otherwise I’d be surrounded by work. But it is nice to think that it’s going to somebody who really appreciates what you do.

Gail: When you actually do your planning and everything for the year, do you set yourself a theme or how do you decide what it is that you’re going to paint?

Ruth: Well, if you go onto my website, my Ruth Clayton artist, you will see that it’s pretty much all seasgates, because that is my ultimate passion. I do like painting hedgerows and trees and that sort of quite loose nature sort of paintings, but my real passion is painting the sea. But when I say the sea, I don’t mean a calm sea, it’s the energy of the sea. I’m totally mesmerized by the ocean and in fact, we have a little caravan up in Scotland, which is right on the coast, and that’s my inspirational, happy place where I can go on my own or take my dog and just do work up there. But I love and I suppose my work is slightly changing because as an illustrator, you basically were picture making. So I’m slowly moving away from picture making and looking more at the textures and the techniques, and it’s becoming slightly semiabstract, and I was looking at the textures in water and I love that. So that’s pretty much what I do most of the time, is it might just be one big wave rolling over, or it just might be waves crashing against some rocks, or it might be waves crashing against the lighthouse. They very often have a structure in there, whether it’s a boat, a lighthouse, a rock, but it’s usually all about the water and how it interacts with that.

Gail: Building water has a very challenging reputation, doesn’t it? I think it’s one of the things that most artists would perhaps look at and say, that was perhaps one of the more difficult things you could choose to paint.

Ruth: Yeah, but I think if you allow the paint to do its own thing and you don’t force it, then the watercolor particularly will do beautiful things. For example, if you have a damp wash next to a wet wash, then the wet watercolor will slowly bleed into the almost dry, damp watercolor and you’ll get like little tendrils and beautiful things will start to happen. You see that in the sea. And I do use white pastel at the end, because that will give that lovely foam and spray. I do flick with white paints. I do use the acrylic ink bottles, but I use it straight with the dropper and I just sort of almost scribble across the bottom to get that real energy. As I’ve been saying, that real vibrance and turbulence of water. And I’ve been doing it for a long time. And I do use cling film, which is fabulous if people are wanting to start with water. Because if you just wet your paper, put your color on, and then lay some cling film on the top and scrunch it up a little bit. Whatever pattern you see is the pattern, how it will dry, and then you take your cling film off and that gives you a starting point for the pattern.

Gail: It’s really interesting to hear you say that, because actually, as you were talking then, I was just thinking about asking if you have any particular materials that you preferred, any particular makes that you preferred. And then you sort of talking about clingfilm. It’s almost from the really sort of art shop. Not expensive, but through to something that you can do very cheaply.

Ruth: Yeah, when I’m talking to people about materials and how to start off, I keep it as cheap as I possibly can. So, like a paint palette of colors, you can make an awful lot if you mix them. In most of my paintings, I use three or four colors, but then they will mix together to create other colors. So I keep it as simple as I can. And also, I don’t use really posh brushes. I don’t use sable because I don’t like the thought of it to start off with. But also I use acrylic. But they are good acrylic brushes. They’re a company called Pro Arty. And I’m just used to what they do, so when they bend over, they’ll spring back to a point where a sable won’t do that. So it is what you’re used to, but it does save a lot of money. So, for example, a size twelve, which is a reasonably big brush in Proarti, would be about £8, whereas in stable you’d be talking about 80, probably.

Gail: Oh, yeah, they’re really expensive.

Ruth: Yeah, and I don’t think it’s necessary. I really don’t. As long as you can get the best quality of the acrylic brushes. And I also use student watercolors as well. There is quite a lot of snobbery.

Gail: About some people are very precious about what they use, aren’t they? It has to be this make or it has to be, I should say, sable. I think actually it’s a similar thing, really, in textile. Some people get very concerned or very hung up on their tools and equipment, their materials. And sometimes I think you can almost get more involved with that than you can with the actual end job, be it be painting or be it embroidery.

Ruth: It’s not saying, isn’t it all the gear? No idea. It is here. And I’ve had people come to my class and they’ve got all this fantastic gear, but you need to know how to use it. And actually, you could just take a quarter of that and you’d get good results. So I don’t think you need to break the bank. And yeah, I do use cling film, I use salt. That was fantastic things for watercolor, if you allow it to do its little patterns. And I use rice, I put rice on it. That’s really wonderful for, like, hedgerows and things like that. So there are things that you just find around the house. And I use four brushes. I’ve got a palette of about seven colors. I use one particular paper. It’s just really cheap and cheerful. I know what it does, I know how you can lift watercolor off it. It’s just boxingford. And I never really vary from that. I don’t, you know, I just think I know what that does. Now, I have treated myself to some Daniel Smith watercolors, which are lovely.

Gail: Yeah. Are they the actual pans or are they in a tube?

Ruth: Always in a tube, because I don’t use pans. I only use pans and half pans when I’m going out working. Just like little sketches, because we think about the little squares or the oblongs, which is the full pans. And if people go and look at my work, you’ll see that I’m not a delicate watercolourist, I’m quite bold. I would never get enough paint out of that palette to create what I create. So I have to use the tubes and then the pans are just for illustrative work and sketchbook work and going out and painting.

Gail: Yeah.

Ruth: But then I have treated myself just to a few in fact, I’ve put some on my Christmas list and things like that on birthday list. But really just the bog standard student watercolour, windsor and Newton or Dale around it have stood me in good stead for donkey years.

Gail: Absolutely. And of course, you get to know what you’re working with, don’t you have a while?

Ruth: Yeah. And in fact, the ultramarine of Daniel Smith I don’t like as much as the ultramarine of Windsor and Newton student colours, because it is so different, because that’s another thing. Different colours and different brands will be different. An auto marine in Windsor and Newton is so different to Daniel Smith, so you’ve got to really try them out and see what they do.

Gail: Yes, and I know that you have. I think you’ve been working with the charity as well, haven’t you, for this day? Would you like to tell us a little bit about that?

Ruth: Yes. Not one particular charity. I tend to look at lots of different ones, but I’m really quite concerned about our planet. I was watching Frozen Planet and I watched all of them. And the last one, I won’t lie, I was in tears looking at what’s happening and what we’re all doing and rising sea levels and why that’s happening and the pollution in the sea. So I thought, well, if I can somehow highlight that through my artwork by donating, I don’t know, 1015 percent of a sale to a particular charity, So I do look at lots of different ones. I look at small organizations that are trying to come up with ideas of how to clean up the ocean to greenpeace and what they’re doing. And then I want to sort of have more documentation by the side of my artwork, sort of without getting too political and on my high horse. But I just want to try and highlight it and make people more aware of the impact of what will happen if the fee rises as it is at the moment.

Gail: Yes, I think we’re going to see a lot of changes and most of them aren’t going to be for the better, are they, over the next few years?

Ruth: Absolutely not. And it’s a travesty. You and I, we can only do what we can do in our own community and in our own house. It’s the big corporations, et cetera, and Westminster who need to perhaps do more, but we won’t get into that. But I just do my bit. I do what I can.

Gail: I think it’s wonderful that you do and obviously having such a deep connection as you obtain with painting something. Do you usually paint from life or do you take a photograph and paint later? How does that work?

Ruth: Well, if you look at my work, it would be incredibly difficult to paint from life. I would have to be turner said that you’d have to be strapped to the mast of a ship and I really want to have to be in the crowd’s nest up there because of the sort of paintings that I do to get that close. I mean, I did go to youis a few years ago with Stewart, and he was really worried about me because I was getting closer and closer because I was looking at the sea through a lens and getting photographs. And he almost wanted to put, like, a lead on me because it was really windy as well up there. So I do take my own photographs, but then I do look at royalty free photographs because there’s a lot out there that you can get. But I only ever use that as an initial idea. I will change the colours. I will include a lighthouse. I will just use part of it. I’ll zoom in, I’ll incorporate it with my own work. It’s only ever a starting point.

Gail: So would it be fair to say that very often your work is sort of an amalgamation of different views rather than one particular one?

Ruth: Absolutely, yes. You’ve hit the nail on the head. It’s lots of different views from different things. And I might have one image that I think I love the colours of that it doesn’t necessarily need to be a seascape either. I can just look at a landscape and think actually those colours would look lovely in a seascape. So I’d use that for the colours. I might look at one particular wave shape, but then I might look at a boat or some rocks and then I will try and put the whole lot together.

Gail: Yeah, I just find that amazing. I can’t actually quite wrap my head around how I do that. Years of practice, I’m sure you got into, possibly.

Ruth: Yeah, maybe.

Gail: I think we can all imagine a scene because we have it unfold before. Is that to try and take a few different scenes and amalgamate them in that way? I think it’s just so skillful. I’m in awe.

Ruth: One thing I can’t do, it’s a real mental block, is if I’m looking at an image, I can’t paint it in reverse. I have to reverse it on my printer, think, oh, well, that wave actually would look much better if it’s coming the other way, I can’t just flip that in my head. I would have to print it out the other way and then look at it that way. That’s an absolute mental block. I don’t know whether that’s the same for everybody else, but I can’t do that.

Gail: In a way, I’m quite glad to find there’s something you can’t do. We’re trying to put the different ones together. Have you ever had such of anything funny happen while you’ve been out painting?

Ruth: Well, not actually when I’m out painting, because usually I try to keep myself to myself when I’m doing any sketching or anything and I don’t interact with people. But there was one little story. It was after I’d started a class and I was telling everybody about the materials, and I said, you will need watercolour paper. Don’t just use cartridge, you will need the real McCoy. And that weekend, and they’ve got my phone number and one of the ladies rang me up and she said, Ruth, I’m here in the middle of the art shop and I’ve got this pad of watercolour paper, but it says not watercolour paper.

Now, to explain to people who don’t know about that, watercolour comes in three different surfaces. It comes in hot press, which is smooth. It comes in rough, which says roof, and then the one that’s in between and it’s the weirdest title is not no T. So Not Watercolour Paper actually is watercolour paper with a slight texture. But she was looking at this really confused thinking it says it’s not watercolour paper. No, that’s okay. It’s not watercolour paper. Yes, I know. It’s saying it’s not. This conversation was quite bizarre. So then I just sort of explained, no, it’s watercolour. And the texture the word not means that it’s actually slightly textured. So that was quite confusing.

Gail: Yeah, because there are a lot of different watercolour papers out there, very expensive.

Ruth: And I’ve been caught out because I bought myself a really beautiful linen type paper. And I did a big tree on here and I thought, yeah, and I’ve got it all planned out, but I didn’t do a little sheet first, so their lines a tail. And I thought, well, I’ll paint that and then I’ll lift out quite a bit of it. And I did this painting and it would not lift off that paper. And I was using the identical paint, so it was obviously the paper. So different papers react to paints as well. When you do any testers or any planning, you need to do it on the same paper that you’re going to be working on.

Gail: Do you use a particular supplier? I don’t mean in the respective wind and you not or something like that, but I mean, do you use a small local shop when you’re looking for suppliers? Yeah.

Ruth: And I will have a shoutout for Ken Bromley. Ken Bromley in Bolton. I’ve used those for years and years and years, and they were family owned business and they moved different premises. But I get all my paper from there. I don’t buy my paints, et cetera. I’ll give another shout out there. Mind you, this company is wholesale, but it’s Abacus Resources and they’re in Carnford, and once again, they used to supply seed of farm. And they approached me when I moved up here and sort of said, well, we’ve got this new little business now in Carnford, and would you like to try this out? So I tend to buy my paints on my brushes from Abacus and I buy my paper from Ken Bromley and then the Daniel Smith wherever. Usually I’d get other people to buy that for me.

Gail: Is it really expensive? I’m a stubborn that’s my ignorance.

Ruth: Incredibly expensive. But there’s one color there which is called lunar blue, and it’s just phenomenal when you mix it, it looks like a mucky gray, then it separates in the palette. Actually, you got to keep mixing it up into like a turquoise and a deep blue. So on the page, as it dries, it separates and the two colors come out and it’s just phenomenal. Yeah, but it’s not cheap, but good quality.

Gail: No. Well, I always think it’s again, whatever craft area that is your chosen area, I think it’s worthwhile paying a little bit more if you’re able to. I know not everyone is, because the pleasure really increases, doesn’t it? If you can use something that’s really lovely to use, that you love, the effect of it makes such a difference to your experience and actually working with that medium or that yarn, that thread, whatever it might be.

Ruth: You’re right. I was talking before about it doesn’t have to be expensive, and it really doesn’t, but it is lovely to add to that. So if you have a birthday or something like that, or you want to treat yourself, it is really nice to think, oh, that looks like a really beautiful color, or I’m going to buy a ceramic palette. Even that because I tend to use like I don’t use a small palette that they call Flower daisy palette. So they’ve got quite big wells, but I just use the plastic ones. But if you want a treat, you can buy a beautiful ceramic one. And it is nice to do that, but it’s not absolutely necessary. You can do really successful work with relatively cheap equipment. Well, not cheap, but cheaper equipment. Somebody once said to me, buy the best that you can afford. I think that’s a pretty good I.

Gail: Know sometimes not that I generally do, but sometimes you go around Aldi, for instance, or little, and they have some of these things, some very cheap art supplies. I’ve never tried, but I imagine they’d be quite hard work if you ever tried.

Ruth: Yes. And the works is another one, and I’m not knocking the works. They have some brilliant stuff in there. But a rule of thumb if you’re buying watercolor paper, if you look at these pads and if it’s got texture on one side in a pad and on the back of that paper, it’s smooth, then don’t buy that. That’s not been made properly. It’s not being pressed. It’s just basically a piece of paper that’s got a little texture on one side and nothing on the other. Fine for practicing and playing with, but when you start in earnest, you do need to buy the best that you can afford. But use of the equipment isn’t great.

Gail: Yeah, I can well imagine. Ruth, it has been I can’t believe that we’ve been talking over an hour.

Ruth: I know

Gail: It has been an absolute pleasure to have you here and to chat to. Obviously, we’ve known each other now for a long time and it’s always a pleasure to chat, but it’s really nice to be able to share with the listeners. I’ve always loved chatting with you, and obviously, I know we’ve talked many times about how you instil confidence in people to do, be it textiles or be it art. So I really hope that our talk today will have maybe inspired one or two people.

Ruth: Yeah, just do it. Stop talking about it. Just have go. But thank you very much for inviting me, Gail. I’m very honored to be on this.

Gail: Absolute pleasure. It’s been a pleasure. Thanks.

Ruth: Thank you.